September 26, 2017

Liturgy for the Non-Liturgical Christian

We like to think that there are liturgical churches and nonliturgical churches out there. But actually what we have is a distinction between churches that are self-conscious about their liturgy and churches which like to pretend they don’t have one.

So writes Doug Wilson in Mother Kirk: Essays on Church Life. And he’s right. He’s right as I observe it from theory and from practice.

Liturgy is making a comeback among many in the the younger evangelical crowd. Yet it’s worth pointing out that most of these youngsters (and older folk too) who think they are moving from non-liturgy to liturgy as a kind of ‘adding to” in their Christian church experience, need first to realise that something entirely different is happening.

For to move from nothing to something has a spark and energy about it that is palpable. You can feel the zing if you have nothing liturgical about you at all, no religious framework that you can draw experience from, and then one week you become a Christian and find yourself in a church that has a set liturgy. Simply put, it’s exhilarating.

But here’s my experience with those who move from a longstanding so-called “non-liturgical” church frame (think the average seeker/attractional church) to a self-consciously liturgical expression of church (either a confessional church, Anglican/Catholic/Orthodox, or one of the newer independent churches that has rediscovered liturgy). Their first taste of such liturgy is like sucking on a lemon. And the expression on their faces as they do it only reinforces that picture.

They find the prayers too repetitive, not to mention far too long. That prayer happens at all is almost a thing of great wonder to them, beyond the usual “Dear God we just really honestly want to say Amen” prayer that they have become used to. Such prayers are offered quickly at the start of the service prior to getting on with the real task of singing repetitively and for far too long.

They find the call to worship and the sending out to the world tedious and slightly self-aware. They struggle with the set format, the lack of anything spontaneous which is, to many in this age of authenticity, the mark that we have somehow locked into God in a way that order does not, even accounting for Paul’s command in 1 Corinthians 14:40.

And the Lord’s Supper every week? Coming from church backgrounds that tack it on, almost sullenly, rather than solemnly, to the end of the service once a month or once a term, it feels extraneous. And what’s with confession, like, all of the time? And reading that same passage from 1 Corinthians 11? What happened to the spontaneous mini-sermon from the leader who weaves their weekly life events into a slightly mystical story about what these elements might mean?

And the length of that Bible reading! A whole chapter? And then a second reading from somewhere completely different that seems to bear no semblance to the first.

Perhaps I am being a bit cheeky. But it makes the point. When we move to a church with a self-conscious liturgy after years attending churches that don’t seem to do liturgy, it feels awkward and clunky.

And it is. It’s as awkward and clunky as a naturally gifted tennis player, who has never been coached, having his or her game broken down by a good coach, in order to build it back up again and improve it. The tennis liturgy that had, actually, served so well for so long, felt safe. But it wasn’t going to cut it on the tour. It would be found out.

That’s exactly the same thing a good liturgical church that has thought through the process, is doing with liturgy. If that church finds itself filling up with people from other church backgrounds who have not experienced clear liturgical frameworks, then awkward and clunky will be standard. But piece by piece, over time, as their “game” is deconstructed and built up again, people rediscover both the joy – and strength – of liturgy not as an end in itself, but as a means to an end.

For you see, liturgy can become an end in itself. Think of the dry, muttered words of the priest in the declining church who neither believes three quarters of the rich liturgy he is delivering, and who would rather shut the church down than have his parishioners actually believe the biblical and gospel gems contained therein.

And for many, sadly, such rote liturgy becomes an art form, a lesson in high cultural superiority, much akin to the famous conductor of all things Bach, Sir John Eliot Gardner, who by all accounts is something of a rogue and who apparently, and in direct contrast to the great JS himself, does much of what he does to the glory only of Sir John.

But when liturgy serves the end of showcasing the wonder and beauty of the Lord Jesus Christ as played out in the divine actions of God through Scripture by the power of the Holy Spirit; when that is central to the goal, liturgy takes on new meaning and gives new meaning.

For it undoes not only the tepid liturgies of the post-liturgical churches of the 20th century, it challenges, exposes and enervates the secular liturgies that chant their mantras to our congregations day in, day out; week in, week out, year in, year out. If you want repetitive liturgy that is all consuming, don’t go to the church, go to the mall!

Jamie Smith makes the observation that when we come to church for worship and we engage in self-conscious and faithful liturgy, it does two things.

First it re-stores us. It builds us back up again in the most holy faith. Why is this necessary? Because the most unholy faith, the messages and glories of the late modern cultural age that we inhabit, grind us down.

The cultural liturgies of the shopping mall, the social media toxicity, the zero-sum game of politics, whether it be in the parliament, the office or even around the family table, all wear us down and deplete us. At best these liturgies offer us a vision of the good life that is a lie, an enticing good news that aims to muffle and suffocate the true gospel. At worst they crush us with a sense of our own failures, or the collective failures of the church.

“You’re on the wrong side of history” is perhaps one of the most toxic liturgies I have ever heard pronounced, and it’s said with such regularity, that those who wish to stand up for biblical ethics in our context, are getting smashed by it.

Such a toxic liturgy requires more than a few songs, a short prayer and a homily to counteract it. It requires something robust to push back against it; something that, week in, week out, verbally proclaims that we are on the right side of history despite claims to the contrary. The resurrection of the Son of God proclaimed in words, and His word visually displayed in the bread and the wine; these are the true liturgies that counter the lies, and build us up.

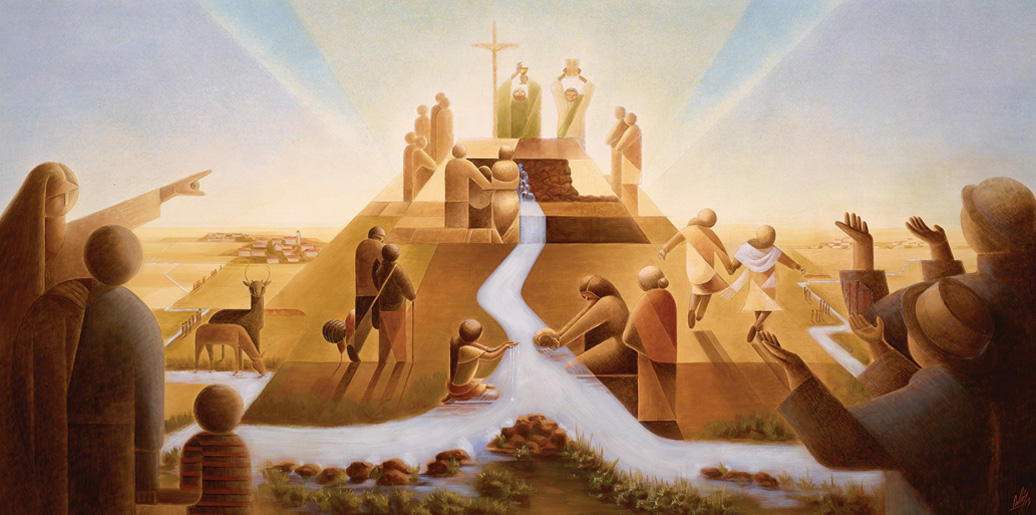

Which leads us to the second observation. Self-conscious and faithful liturgy re-stories us. We gather to hear that we are in a different story to the stories that we have been plied with all week long. We gather to hear the story that begins in a Garden and ends in a City and that has a vision of the good life and of flourishing centred around the worship of the Lamb, not the worship of the self.

Good liturgy walks us through that story. Not all of it every week. But enough of it over time that we gradually can become impervious to the alternate stories of sex, power and money that are constantly reinventing and re-presenting themselves to us in various guises. Good, self-conscious liturgy is not the sum total of what we do when we gather in various formats as church, indeed it would be strange if it were, but it must the planet at the centre that pulls everything else we do into planetary alignment.

Good liturgy becomes embedded in us so that when those lies come to us as truths, the sheer weight of the truth in us casts them aside, and we find ourselves living liturgically in the gospel due to the sheer length of time we have spent proclaiming true liturgy. Good liturgy doesn’t pretend to be all of our worship, it simply prepares us for a life of worship that is directed towards what is worthy of our worship. Good liturgy sends us out after gathering us in with a clearer sense of the story.

The decision by many churches to cut liturgy at just the time the cultural liturgies were ramping up in energy, was to the church what uni-lateral disarmament was to politics in the 1970s and 1980s.

Both are suicidal and naive. Unilateral disarmament was built upon the airy optimism that should we disarm, then our enemy will have no choice but to disarm also. The final few years of the Cold War showed up that for the fallacy that it was. So too with liturgy. The enemy is not for turning.

It’s no surprise that those churches that self-consciously cut liturgy from the program often found another liturgy creeping in to take its place; one that apes the consumer liturgy of the mall. Sure it fills a few churches for a while, but what we draw people with we draw people to. The consumer moves on when the product doesn’t satisfy. Or cashes it in altogether for something that seems brighter and better.

The goal of liturgy is to reorient our desires in a desire driven world. And if you’re struggling with liturgy in a church setting, or you’re wanting a more authentic expression of worship, think back to that tennis player.

The goal of the great players is to reach a stage of muscle memory and unthinking action that sees them reach that serve across the court that they should, all things being equal, not be able to reach, could not be able to reach. But their practice over years means that all things are not equal! They have built a reaction time within themselves based on how they have rewired their neural pathways.

And that’s the point. Liturgy is supposed to become second nature; both in its formal arrangement in church gathering, and in its enactment as a liturgical lifestyle out in the world. Just as the other liturgies intend to do. Retail therapy becomes second nature. Online gambling or porn addictions become second nature. The presumption that the satisfied self is our great goal becomes second nature. These are all enforced as we do them, as our plastic brains forge new and easier pathways for them to follow.

There is no neutral. Liturgy exposes the fallacy that there is. There is no liturgy for the non-liturgical. There is only a true liturgy to counter the false liturgies that call us to their visions of the good life.

Written by

There is no guarantee that Jesus will return in our desired timeframe. Yet we have no reason to be anxious, because even if the timeframe is not guaranteed, the outcome is! We don’t have to waste energy being anxious; we can put it to better use.

Stephen McAlpine – futureproof

Stay in the know

Receive content updates, new blog articles and upcoming events all to your inbox.