September 4, 2018

Greg’s Book Is Good For You

My wife Jill and I went on our first date 25 years ago next week. Half of my life time ago. It seems impossible to conceive of life without her. What would I do if I lost her either through stupidity or tragedy? To whom would I turn in times of trouble and joy? Who would I wish to serve? Who would listen to me as she does?

The existential nature of those questions lies at the heart of Greg Sheridan’s latest book, God is Good For You: A Defence of Christianity in Troubled Times, which itself begins with a wonderful, and revealing question:

What will it mean for us when God is dead? Who, then, can humanity converse with, when we lose our oldest friend?

Among the reasons that led to Sheridan, the foreign editor of The Australian newspaper, writing this book is that existential concern. The loss of God in our secular culture will leave a huge hole that cannot remain empty. It must be filled. But by what? What would be lost? What would be gained? And would we settle for that exchange?

If you come to Sheridan’s book looking for philosophical, historical, pragmatic, social or other reasons for believing in God, you will find them. Greg insists that while belief in God is good for you, that pragmatic fact is not reason enough to believe. Believe it because it’s true! If it’s not true, then don’t. Which all makes sense. When it comes to journalism, Greg is old school, ideological activism wasn’t included in the job-description, certainly not in lieu of commitment to facts.

So Part One is a great, informative, and well-reduced, apologetic for all of those who would sign off on the Apostolic Creed. If the interested unbeliever is reading – and I suspect many are – there’s nothing opaque here – it’s crystal clear. One wonders how Greg would survive in the increasingly torturous world of theological publishing, given his eschewing of weasel words.

This first section contains an overview of the nature of belief (and unbelief). It includes a take down of the new atheists (and from a public figure in Australian life not merely a peripheral Christian perspective); a apologia describing how the foundations of Western human rights, rule of law and politics, is grounded in the Christian faith; a robust analysis of the problem of evil, inside the church (think sex abuse scandals) and outside the church; and a pithy overview of the Old Testament, including excellent exegetical read of the books of Ruth and Jonah.

In one sense this is stock standard stuff. Go to Christian bookshop Koorong and there are a dozen titles that cover the same territory, sometimes more technically proficient, but never as well written.

But you’ll never buy those same books at Dymocks. Never see them on the shelves at the ABC Shop. You won’t pick them up at the airport sales stands on your way to Melbourne or Sydney.

They exist in the Christian ghetto, specifically our Christian ghetto, in which we laud our heroes, our playboys of the Western world, who turn out, as we deeply suspect they are, to be mere provincial champions who would not cut it in the big leagues.

Hence Greg’s book is different, because Greg is different. He’s a public figure in Australia who is on first name basis with many major politicians, political players, influencers and public heroes, both here and overseas. His own influence in Australia is substantial, reaching millions each week. He’s a big league player.

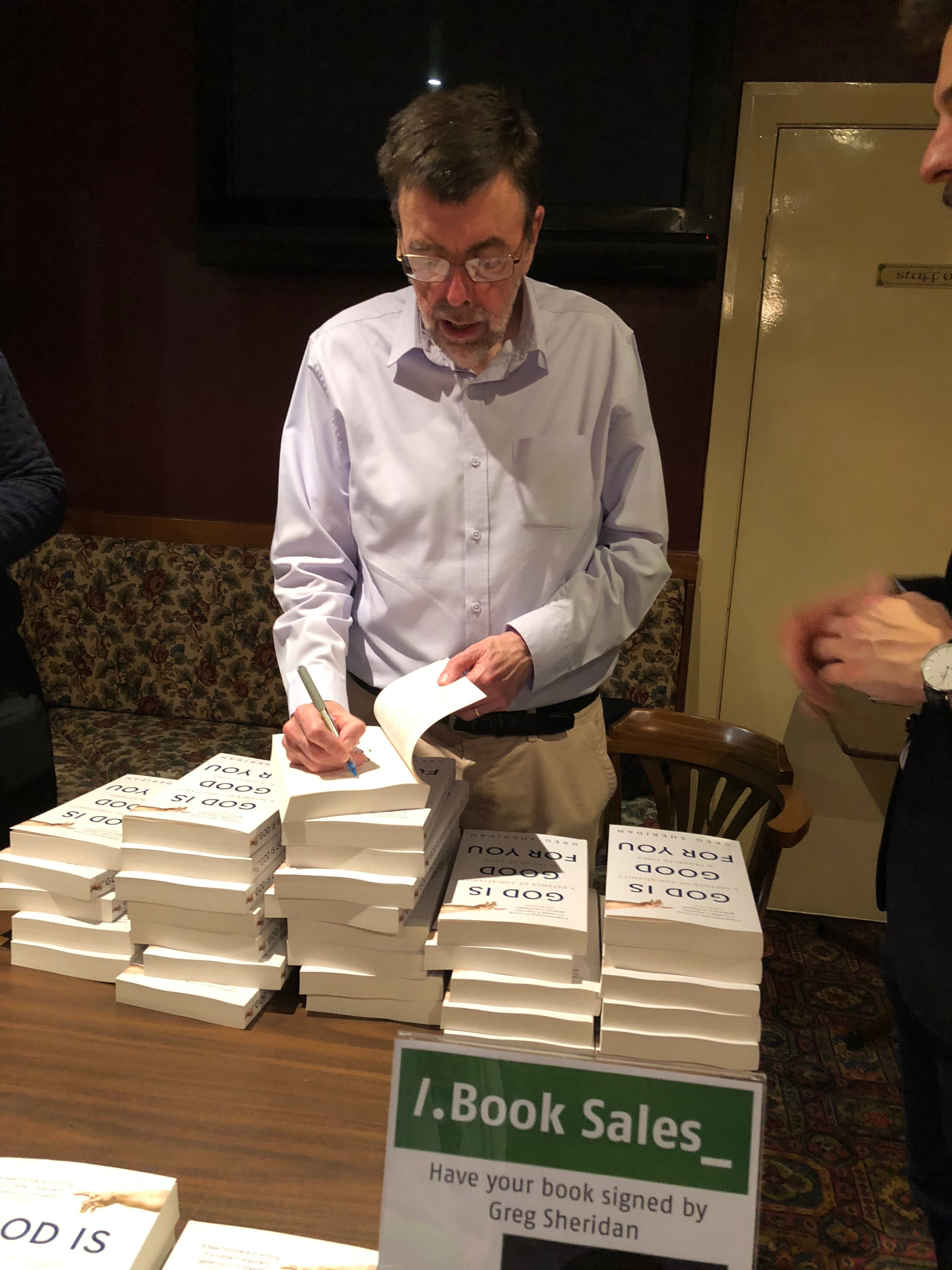

So last night, at the Perth launch of his book, which I MC-ed, the bookseller setting up the stall remarked at how well Sheridan’s book was selling, and how his store had underestimated its popularity. It’s fairly flying off the shelves. Secular, non-religious people are reading it! They’re responding to it.

Which makes Part Two such a brave and insightful decision. Rather than lamenting the obvious decline in Christian religious observance in Australia, or simply bemoaning how hard it is to be a Christian in the increasingly hostile public square, Sheridan presents a future for Christianity, a changed and chastened future, that highlights the beauty, simplicity, earnestness and desirability of the Christian religion.

Sheridan takes us on a Cook’s tour of the inner spiritual life of some of Australia’s best known politicians, showcasing not what the activists want to know – public statements on where they stand vis-a-vis the increasingly bitter culture wars-, but what our politicans think of God, if they pray, how they view life after death.

And the results are surprising. And surprisingly tender. Inured as we are, cynical about the role of politicians in our public lives, the likes of Bill Shorten, Malcolm Turnbull, Andrew Hastie and Penny Wong come across as thoughtful, humble and self-deprecating.

Not that these were puff pieces. By no means. As Greg observed last night, just getting politicians to speak about their faith was like pulling teeth. They’re battle scarred. They’re wary of a hostile media, which as former NSW Premier, and devoted Catholic, Kristina Keneally observes in the book, is far less religious than politicians who, in turn, are more religious than the general population.

And since the media mediates, then the most sanguine of faiths among our leaders can be presented to us in print and online, as a sure sign of manic fundamentalism. (Exhibit A: Scott Morrison’s treatment: crazy Pentecostal hand-waving, tongue speaking ignorer of all kids on Nauru).

But there are nameless wonders there too. The Benedictine monastery where the life of prayer and discipline chafes against the godless self-focus of our digital age. The evangelical shoots that are re-forming and reshaping to fit the secular landscape, all the while clinging strongly and lovingly to their theological convictions.

But it’s the practices of love, of empathy in suffering, and indeed modelling suffering for the sake of Christ, that most comes through in this later part. It’s a defence of Christianity indeed, but neither angular nor angry.

My own particular copy of Sheridan’s book is akin to a school library copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover circa 1956; it tends to fall open at certain pages, namely the couple of pages with my name in it. Which proves little about me, except as confirmation of the doctrine of incurvatus en se; that sin is the heart curved in on itself.

I thought I came off pretty good in those pages, as did my boss and colleague Rory Shiner. But here’s the existential moment. The true revelation of this book was Greg’s friendship with an Anglican rector, Rod McArdle in Melbourne who, against the secular odds, has maintained his deep but gentle faith in the midst of great struggle and grief.

Against the odds of a son born with major disabilities; a wife who died several years ago, and the growing realisation that at 67 he can no longer care full time for his beloved son.

When told by Greg of Australian philosopher, Peter Singer’s argument that severely handicapped babies could be ethically killed if their parents did not want them, Rod McArdle replies:

My response is one of deep sadness – sadness that the writer misses the intrinsic value of every person, irrespective of what any given society might deem to be their “handicap”. That worth flows from each person being loved by their Creator…everywhere [my] son goes he is a beacon of light and love, and blesses all who have the privilege of caring for and/or interacting with him.

Did e’er a father love a son like that?

Yes. God the Father loved his only begotten Son with a depth that Rod’s love, though it echoes this truly, merely echoes. Yet instead of self-serving, the Triune God gave; gave of Himself to us and for us, in a way that is designed to astonish us, and break our hard hearts.

For in the end, fine sounding arguments, as Greg offers in Part One, can only go so far. But when we’re at the risk of losing our oldest friend, and we’re casting an eye around nervously at the philosophical and ideological swill that would offer their grubby hand as an alternative, it’s the cri de coeur that needs a response.

And in a universe in which US Supreme Court Justice, Anthony Kennedy can say is “lonely” and in which our needs for love can only be filled by another, Greg presents God not only as good for you, but as the essential lover and friend, besides which all other lovers and friendships pale.

Written by

There is no guarantee that Jesus will return in our desired timeframe. Yet we have no reason to be anxious, because even if the timeframe is not guaranteed, the outcome is! We don’t have to waste energy being anxious; we can put it to better use.

Stephen McAlpine – futureproof

Stay in the know

Receive content updates, new blog articles and upcoming events all to your inbox.