October 22, 2022

Some Short Thoughts about Kurt Cobain, Nick Cave and a Ministry Fail

Let me tell you about a pastoral ministry fail of mine. A small one, nothing major, but, in hindsight, a fail nonetheless.

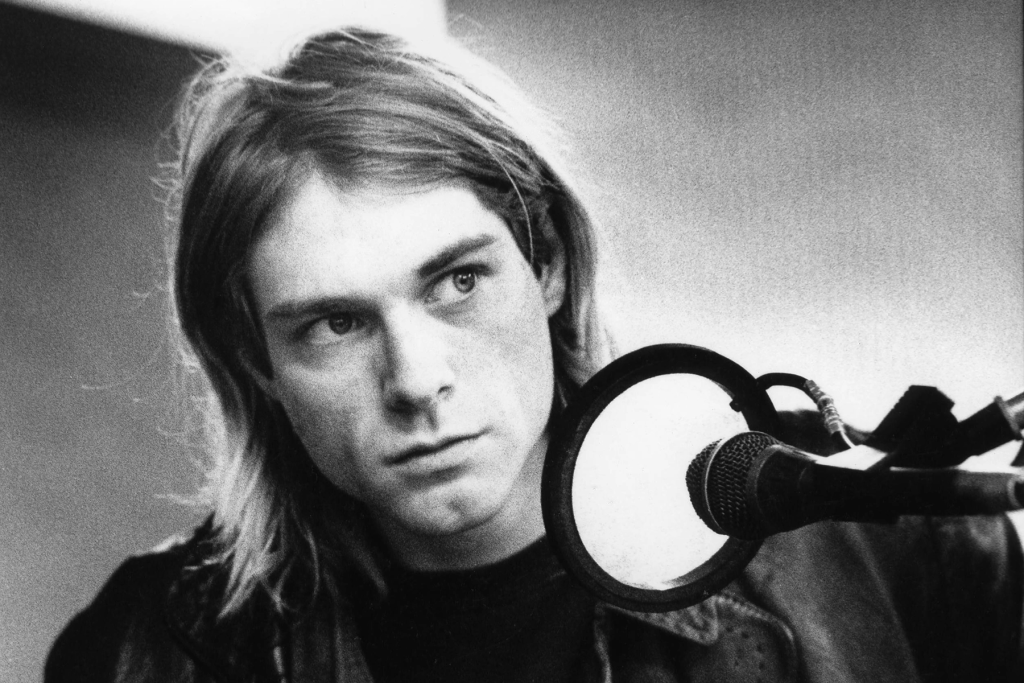

It has to do with Kurt Cobain. Or at least it has to do with his death.

I remember the day that Kurt Cobain died. Many of my generation do. My generation is the X Generation seemingly defined to miss out. The Boomers have clung to power in politics and corporate life so long, that they’re ready to hand it all over to the second biggest generation in the Western world, their Millennial children. We waited out turn in the queue, and someone stepped in in front of us. Pushed in. And encouraged to do so – as ever – by their parents standing in front of us.

We X-ers are the children of the so-called Silent Generation, those too old to be teenagers and early twenties at Woodstock, yet young enough to remember the privations that followed the Second World War. If our parents were not heard because they were silent, we are not heard because of the white noise of technology that favoured those following us, and which has drowned us out. Or because of the white noise of our own insecurities. Perhaps a bit of both.

Kurt would have been my age. Born in 1967. 55. And he could have gone one of two ways had he survived. He could have been Dave Grohl, a reinventor and reinvigorator extraordinaire, whose second band career in the Foo Fighters has been nothing short of astonishing. A career in itself, in which the Nirvana tag, if not fallen off, is at least faded and fraying.

Or he could have been his other bandmate, Krist Novaselic, whose post Nirvana career has been meandering and thoughtful, but ultimately a long riff on the past. Grohl is all hair and tattoos – the ultimate rocker. Krist is bald and big, with a beard and moustache that suggests King George V. His face would not look out of place in the National Portrait Gallery, albeit one that need be explained.

Some Grohl exceptions aside, as a generation we have become Krist, noteworthy and vaguely recognisable, but our headline obituary will require more than one reference point to explain who we were.

But back to Kurt. The grunge rock musical rule breaker who became the cliché bursting onto the scene, who blew up before blowing out. By blowing his head off. It shocked us all. We were totally bereft.

Well I was not totally bereft. I was saddened and felt the loss. But you know, there was Jesus. And there was ministry. I was working off my own Cobain slacker angst, employed gainfully – and finally – by a fairly theologically liberal mainline church in the centre of a vibrant Australian city. It was my first ministry gig. I was a greenhorn.

The church – old and impressive for such a young city in such a young colony – sat at the intersection of two main streets in the CBD. It was a fixed and focal meeting point for many young people in the days before smart phones could guide you to some ephemeral pop-up shoe store that sells the retro trainers I would have worn back in the day.

And so, as if by bat signal, the day Kurt died it became a meeting point for a section of my generation to congregate and mourn. There they gathered, all flannel, ripped denim and Converse, weeping and carrying the odd candle. Looking for somewhere to pile up their grief and find some meaning.

And that – still, quaint though it sounds now – meant a church. I was the Youth Pastor of the church, which like many city churches operated a mission that covered all sorts of social justice ministries, financial planning services, free counselling, legal advice. It was impressive.

Somehow these young grief-stricken young people found their way up the elevator to my office. Somehow they knew that someone in a church might have some idea about how they could express their grief, and then park their grief. And somehow that someone was going to me.

Let me tell you about me at that time. Young, eager, sincere, and shocked by the liberal framework of the place I was working. My theological convictions have never left me in the time since I worked there, in fact they have deepened. But I was not sure where to park them in this place in which my superiors felt, well, felt superior to notions of unabashed transcendence, the miraculous, and the increasingly challenged ethical convictions that followed in their wake.

And I was cautious. Cautious about many things. Cautious, as I look back, not so much because of my theological divergence from those who employed me, but cautious because of that white noise of insecurity that I spoke of earlier.

And cautious too, when those grieving young women – and they were all young women – asked if I could help them hold a short memorial service in the church for Kurt Cobain, which they would not only attend, but would organise, and over which I would preside. They wanted to do something – something religious. Well not quite religious – and therein germinated by insecurities that flowered into the response I gave – but something transcendent. Somewhere to park the grief. Somewhere to wail.

And I demurred. I loved Nirvana as much as the next bloke – though I hesitate to think that we were blokey in anyway. For yes, there was Jesus and there was ministry, but there was also my preference was for REM and their curiously asexual talisman Michael Stipe. I needed their ambiguity more than I needed Nirvana’s animosity.

But, nonetheless, I said no. I said no in an awkward, but orthodox way. I explained to them – lamely – that I didn’t think it really appropriate to hold a memorial in the midst of all that stained glass, mahogany and plaque memorials to generations who died by the guns of others and not at their own hands.

Well not that I put it completely like that. But somehow it felt transgressive to say that I would do it. Kurt would have filmed a video in that church building if he could, shredding the very vestiges of its seriousness with the nihilist, painful ironies of those slow, low growls we are now familiar with.

Those slow, low growls that would rise to an anguished, angry shriek before being liberate into the shattering shards of alternate primal screams, before recovering for breath and doing it all again for four more minutes. No, not in this church with its pipe organ and bells. It was too jarring. I had learned to keep my art and my heart apart. This was a serious building on serious earth indeed, as Philip Larkin puts it in his stunning poem, Church Going.

And so they left. Left never to return. Candles in hand, flannies hanging out over their slacker jeans, they took the elevator out of the building and back into the clanging city streets. And I felt a queasy unease that somehow I could have helped them if I had wanted to, or at least if I had had the theological and pastoral acumen/bravery to know exactly how.

Well, I say, never to return. Never to return – to me. A week later I discovered that they had indeed held a vigil and service – albeit a secular one – in the church building. Exactly the one they had wanted when they had described it to me. My new boss, the new senior minister, a kindly man with integrity, love, and not an ironic, pop-cultural bone in his blue-suited, Ned-Flanders-moustachioed body, granted them their wish. And presided over it for them. It was black candles and red-checked flannel shirts at twenty paces, all muted by the sun-stained coloured apostles refracting the afternoon light through the church glass.

And when he told me, I felt a pang. A pang not of jealousy that the young people had come to the antithesis of young in the form of a socially progressive, but culturally innocuous churchman, but a pang of regret that I, in my pastoral “greenhornery” had missed an opportunity. An opportunity that if it presented itself today upon the death of whatever stream service superstar might have died, I would grab with both hands.

For it turns out, that in line with Larkin’s poem, many young people today, it would seem, are looking for some serious earth, and if the only serious earth they can find has a serious house built upon it, then so much the better. Sure they’re not necessarily looking for old time religion, nor are they anything but dismissive of its more culturally conservative and theologically orthodox expressions. But they are looking for serious earth nonetheless.

They are looking for a sense of transcendence. A transcendence that ushers in the counter-intuitive sense of significance in the face of one’s own insignificance. So many of my generation know what non-transcendent insignificance feels like. Maybe our successors wish to avoid our fate. And not – at least yet – in any orthodox Christian way. But they want something.

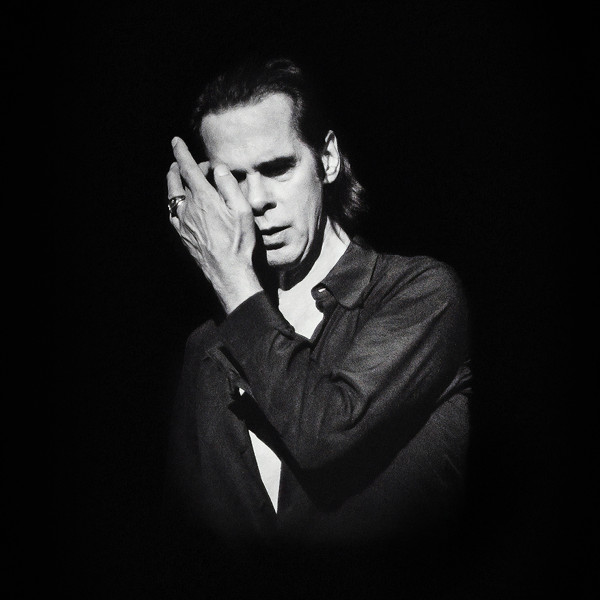

Nick Cave, a man who would surely be Kurt Cobain’s Kurt Cobain, puts it like this in the astonishing printed interviews Faith, Hope and Carnage, with Sean O’Hagan :

I am not saying secularism is an affliction in itself. I just don’t think it has done a very good job of addressing the questions that religion is well practised at answering. Religion deals with the necessity of forgiveness and mercy, whereas I don’t think secularism has found the language to address these matters. The upshot of that is a kind of callousness towards humanity in general…Whatever you think about the decline of organised religion – and I do accept that religion has a lot to answer for – it took with it a regard for the sacredness of things, for the value of humanity, in and of itself. This regard is rooted in a humility towards one’s place in the world – an understanding of our flawed nature. We are losing that understanding, as far as I can see, and it’s often being replaced by self-righteousness and hostility.

Kurt Cobain was not the last of his generation to commit suicide. Still won’t be. I read recently that in 2017 in the UK, the most common age to kill oneself was at 49 years old. More than two decades ago it was 22 years old. Generation X both times. Something went wrong with my generation. And it stayed wrong. We didn’t grow out of suicidal ideation and actualisation. We grew into it.

Perhaps Cave is right. Our parents left us with only the detritus of their own religious tidal retreat. Sure we rummaged around in the attic, making do with a few odd candles and the occasional scrap that hinted of a visit to serious earth at some time. But that simply wasn’t enough to hold back the banshee secular forces that have assailed us.

Here I am some thirty years later, still with Jesus and still with ministry. It might be better to say that Jesus is still with me. He’s been faithful as a rock. As the Rock. And for that I am eternally grateful. Where would I be without him?

But gee, the journey has been tougher, more bracing and challenging, and more enervating than I could have barely begun to imagine back there in that serious building, a building that even as I worked there, was unwittingly preached the virtues of the secularisation project we find so dissatisfying.

And the pastoral ministry fails I have made in those intervening years puts that first cack-handed effort in the shade. Yet I am still here, reading Cave’s words and wondering how anyone copes at all without something to tether themselves to as greasy grief-scum of life in the imminent frame builds up on their lives.

The hard secular shell seems almost impervious at times. And when collective grief does strike, as it did with the death of Kurt Cobain, a younger crowd looking for meaning and answers upon the death of their prophet will most likely not land on the doorstep of your church with candles or their equivalent looking for a priest or a minister. They will most likely not want you to do something religious to soothe them, because they most likely have no clue what something religious actually looks like. Not in any traditional sense at least.

But if they do, perhaps hold that first orthodox thought, that concern about the transgressive nature of meeting their request. Hold that thought, imagine how you might invite them, perhaps for the first time in their lives, into a serious house on serious earth, and say yes.

Written by

There is no guarantee that Jesus will return in our desired timeframe. Yet we have no reason to be anxious, because even if the timeframe is not guaranteed, the outcome is! We don’t have to waste energy being anxious; we can put it to better use.

Stephen McAlpine – futureproof

Stay in the know

Receive content updates, new blog articles and upcoming events all to your inbox.