November 8, 2023

Actually Max, the post-Christian West IS Babylon: It just depends what you mean by it.

I wasn’t able to attend the 2023 Freedom For Faith conference recently. I did attend the 2022 version where I was one of the keynote speakers, whereupon I promptly got COVID (my first awful round) on the trip back.

I was also scurrilously misquoted by The Financial Review, whose reporter made me out to be a racist, by completely misunderstanding the example I gave, due in no small part to his lack of a good education.

So I missed the 2023 version (not through illness or fear I might add). Pity. It sounds like it was a cracker. Nuanced and helpful, and well pitched.

However I do want to push back – ever so gently – on one of the frameworks being offered by Max Jeganathan, who works with the Centre For Public Christianity (CPX). Given the talks are not yet up on line, my quotes below are from the online Christian news site, The Other Cheek. So I don’t want to say more than the quotes will allow me. Max does a good job of undermining the “Athens” framework which assumes that, given the right audience and a good intellectual package, we might win a hearing.

That, he says, misunderstands the nature of how we engage in public debate today:

This idea of a plural democracy and a plural liberalism is an operating in the purest way that it possibly could. All ideas are not welcome in the public space. So we are not in Athens.

Well I’m clearly not going to disagree with that as I’ve written about that – and often.

But not Babylon? I’m not so sure, and I’ll explain why. But first here is Max verbatim (or at least as The Other Cheek quotes him).

We are not in Babylon if for no other reason than simply the fact that Babylon was pre-Christian and this society is post-Christian. And most of the arguments that are happening now are happening at the level of ideals, irreducible concepts at the grassroots of civilisation, questions about what it means to be human, why we’re here. Purpose, meaning identity, morality. There’s our first principles. Babylon was just cutting people’s heads off at the second principle level. It was operating at the level of ideas, not ideals. Ideas are just suggestions as to a course of action or thought. Whereas ideals are fundamental principles that reflect a particular conception of the good or the good life. And so this is not Babylon in the way that Babylon was Babylon. And trying to stir people up in our communities and in our churches by telling them that they’re in Babylon is wrongheaded and it’s irresponsible. That’s bad theology, it’s bad politics and it’s unread history.

Well for a start, I think that perhaps Max hedges his bets by saying this is not Babylon in the way that Babylon was Babylon. And that’s what he gets right. I really like that difference he highlights between “ideas” and “ideals”. (You can hear me trying to nuance here, as I wasn’t there for the talk).

And that’s what he gets wrong too (certainly in my reading of it). I don’t think that most of us using this motif are actually saying that this is Babylon of the 5th century BC, where God’s people navigated the exilic life before returning to the land, and where we are at risk of decapitation. I think it’s possible to be in a Babylon of ideals as much as a Babylon of ideas. The hermeneutic challenge is to show how this is the case, rather than to dismiss the category entirely.

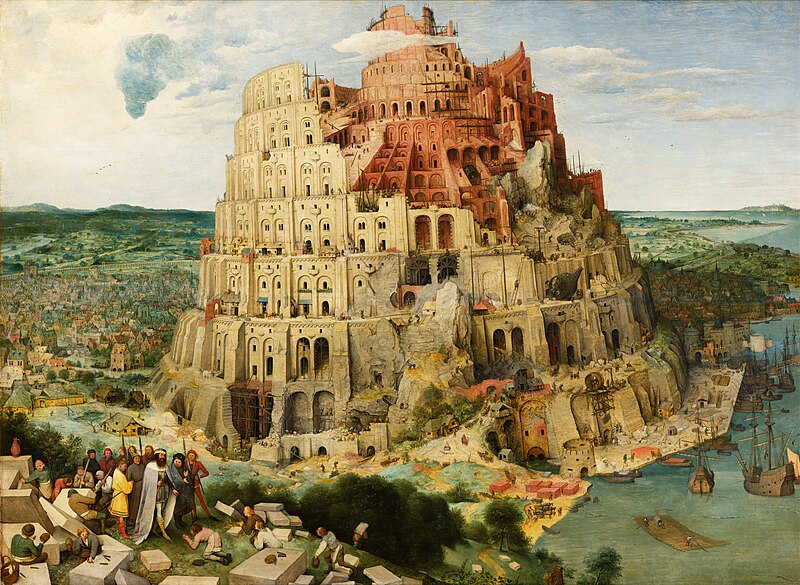

Babylon is a Biblical Category

The main reason I think we need to keep the Babylon motif is that it is biblical! The New Testament uses Babylon not as a carte-blanche “this is that”, but as a lens through which to view the Christian experience in the Roman Empire, and by extension, every Christian experience (more of that later). Granted “Babylon” was a coded way of saying “Rome” when it was unsafe to do so, but by the time you get to the Apocalypse of John, the idea that the empires of the world are Babylon is fairly hard to ignore.

Yet Max asserts that is “bad theology’ to say that what we are experiencing is Babylon today. I think he is wrong at this point, simply because it’s biblical to use the framework. That we need to explain it well to our people, no doubt of that, but to say that it’s bad theology is itself wrong. My experience in using the Babylon motif is that once I had explained it to people, and how it worked not as a direct correlation, but as a concept, they went “Ah yes, that’s it.”

That made the book of Daniel a safe, useful and pastoral text to employ. And, not to put to fine a point on it, when people ARE losing their jobs, or worried about how the HR department is going to handle their commitment to a biblical anthropology, then it’s slightly irresponsible pastorally to say that all that is happening is that they are being “stirred up”.

If it’s merely the case that the framework is useful for pre-Christianity and not post-Christianity then that’s a huge framework to just jettison. Would it not be better to ask of the text of Scripture “Why is it using Babylon?“. Even hundreds of years after Babylon has long gone, the lament in Revelation 18 from the kings of the earth at Babylon’s demise has a distinctly future element to it.

Peter also uses the term at the end of his first letter, code-language again for Rome, when he says “She who is in Babylon, who is likewise chosen, sends you greetings” (1Peter 5:13). I’m fairly sure his readers were not assuming a literal Babylon at that point. They understand the allusion.

The So-called Third Way

Now Max, and clearly John Sandeman from The Other Cheek, wants to hose down the more strident “head for the hills” attitude and proclamations from Christian leaders in Australia. And I note that John calls out Martyn Iles in this regard in the actual article. I think that’s a cheap shot.

In his observations about how Christians engage with the culture, Max sees neither Babylon nor Athens, and hence is, perhaps unsurprisingly, an advocate of the so-called “Third Way”. Some other hybrid city perhaps.

The “Third Way” is that tactical response when doing public Christianity by seeking enough common ground to gain a gospel hearing in a post-Christian culture that Tim Keller so famously espoused. It is decidedly politically neutral and evangelistically driven, though it has implications and desires for the public square. So it’s a “neither this” (accommodation) “nor that” (passive isolation/active aggression) in terms of how we engage our culture.

The premise is that we can gain a hearing in our cultural times by undertaking the “diagonalisation” process that is championed by that most worthy of books, the winner of Australian Christian Book of the Year 2023, Biblical Critical Theory, by Chris Watkins. It’s a great book, and Chris is a great man. It’s probably the most intellectually rigorous book ever to have won that award.

But the assumption that the “Third Way” is the way, has come under pressure in the US from the likes of Aaron Renn and James Wood, who believe that it was a tactic for a neutral world. However, having moved into a more negative world, Renn, Wood, and the likes of Australia’s own Simon Kennedy (who I’ve been with the odd run with and chatted about this with), believe that this is a misguided approach.

We’re not dealing with rational frameworks of thinking any longer. We’re dealing with visceral gut feelings that override any sense of a need to discuss difficult topics with people with whom we disagree. Much better to shout them down, or better still shut them down. It’s a negative world which requires different tactics. Not a different stance, by the way. Winsome is still a thing with Renn et all, but to suggest winsome will win tactically is different to saying it should be our stance.

The real nuance, however, is not some third mythical city that we approximate. No, the real nuance is that Babylon is both brutal and beguiling at one and the same time. And that’s why I think we need to keep the motif.

Babylon is Brutal and Beguiling

The real nuance is that Babylon is both brutal and beguiling. And it is brutal and beguiling to saint and sinner alike. Always was and always will be. Not always in the same ways, but definitely with the same root causes. And those root causes are as ancient as sin itself. To shy away from the Babylon motif intimates that perhaps we, in our modern lives, are more sophisticated and nuanced ourselves than other generations.

In the Apocalypse of John, what comes across is that Babylon loves money, sex and blood. Is addicted to these three things, and is more than happy to bring them together in some form of unholy trinity. And to do so across time and space. There’s a sheer animalistic nature to Babylon, which only an apocalyptic movement will reveal. You cannot read the text of Scripture without seeing how brutal Babylon is (Rev 17:1-6, 18:1-19:4).

Yet also, beguiling. It’s not as if Babylon does not reward those who seek its favour. It’s not as if the kingdoms of this age are not also lining up for money, sex and blood in interesting and new ways.

We only have to look at the prosecution of legislation in our own governments that take a certain glee from laws that kill the young, the elderly, and increasingly the lonely, sick, mentally ill etc, and which employ government agency to do so. If that no longer shocks you, or you think it is somehow nuanced, then Babylon may have gotten under your skin.

Which is also the point: Babylon is beguiling enough to entice God’s people too. And indeed that’s what we read in the early chapters of the Apocalypse, with the churches of Jesus Christ being overcome by money, sex and blood themselves, rather than overcoming by the blood of the Lamb and the word of their testimony (Revelation 12:11). The lessons are clear: The church itself can fall in love with Babylon, and celebrate its ways all too readily, and indeed baptise them, renaming them as God’s city when clearly – if we look with spiritual eyes – it isn’t.

And we all need to take care. The progressive church can point out the obvious financial idolatry of some in mainstream evangelicalism, while the conservative church can rightly point out the obvious sexual idolatry of progressive churches (both declining mainlines and the likes of the newly formed Open Baptist group in New South Wales, which will surely go into decline also).

Babylon Is a Spiritual Reality

But the whole point surely is that Babylon, ultimately, is a spiritual reality, whether we believe we inhabit a physical, political or cultural version of it or not.

And that’s what makes the framework so important for us to keep. In a sense there’s something deeply secular, deeply non-transcendent if you like, about refusing this city as a way of describing the world we inhabit. It’s that understanding of Babylon that ought to capture our imaginations. I’m not saying Max is those things, but losing Babylon in our discussions risks reducing our solutions to the immanent ones.

We don’t merely inhabit a 21st century version of 5th century BC Babylon (all bright and shiny on the surface, and seething with money, sex and blood behind closed doors). No, there’s a spiritual Babylon that needs to be addressed, in fact HAS been addressed by the cross of Jesus.

To lose the Babylon framework or diminish it somehow, in order to keep the edges a little tidier, or more nuanced, or at least keep crazies from taking it hostage for their own devices, risks us creating an apologetic, and devising solutions to our current spiritual crises, completely within the immanent frame. And hence completely ineffective.

The biblical writers are nowhere near as squeamish as we are when it comes to calling out the unseen. And I think once we frame our apologetic task purely within the visible world (this is Australia and hence not Babylon or Athens), then we are falling precisely into the same error – or at least a major error – that has enervated the Protestant church in the West these past fifty years. Whatever this nation is, and whatever city we live in, there is a Babylonish spirit behind it all that brutalises and beguiles.

The whole point of the Babylon metaphor is that there is a grimacing skull behind the smiling face. Every city is Babylon. Every brutality. Every beguilement. If we don’t put a spiritual lens over the lens of our cultural reading glasses then the solutions we come up with will be mostly material ones: better arguments, stronger public institutions that value our faith, government safety, whatever.

And while I do think that Christians should work hard towards a more healthy public square (though even they disagree on what that looks like), this is not our primary battle. Whatever has happened in mainstream Protestant churches in Australia and across the West in recent decades, the loss of any full-blown commitment to a public declaration of an unseen realm would surely be one of our greatest.

In an effort to be seen as reasonable, or at least not as wacky as that Pentecostal woman in accounts who keeps asking if she can pray for you, we’ve submitted ourselves to an immanent frame. In order to play the game in Babylon for as long as we can, we’ve put our hands up and said:

“Okay, let’s argue this on your terms. Let’s ignore the spiritual reality of Babylon in order to get a hearing.”

In doing so we have, I believe, neglected the biggest pastoral and evangelistic tool in the tool-box: the reality of the unseen realm. Maybe we just need to weird it up a little. Maybe, as pastor, I need to explain to my people that they are going into Babylon tomorrow whether they are beguiled by it and are successful and get a huge pay raise. Or whether they are brutalised by it, losing their role at work, or risking their reputation because of what they believe a woman to be.

Here’s where our future traction might be: Weirding it up a little. Taking our first stance towards our moment not from a psychological, cultural, political or even religious framework, but from a spiritual one rooted in the unseen realm. Just as many Christians who have had no power, or who risk losing it down the centuries, have had to do.

That’s why, I quoted the “negro spirituals” songs of the slavery South in my talk last year at the Freedom For Faith 2022 conference, you know, the one I was misquoted on. How did their song go as they worked the fields?:

“Swing low, sweet chariot, coming for to carry me home.”

They sang that because they knew they were in Babylon, even as their slave owners drove the buggy to church every Sunday.

The weirdest, wildest thing we believe in Babylon is not that two gay men cannot get married, though I firmly believe that in the biblical definition of marriage, they cannot. That belief may – or may not – get you cancelled on a social media platform. It may – or may not – see you sidelined in the office and refused the promotion you’ve worked hard for.

No, the weirdest wildest thing we believe in Babylon is that one day King Jesus will peel back the sky, as your fellow work colleagues on Level 26 stare at that sight in equal doses of amazement, horror and wonder. On that day the spiritual reality for so long invisible, becomes visible. The spiritual hunger – and spiritual anger – of the 21st century modern West demands that we start declaring invisible realities behind visible frameworks. It might not work in the short term, but as a long term strategy in a culture that has already rejected the New Atheism as untenable and unpalatable, and clearly unsatisfying, it might just work.

Babylon doesn’t want you to believe that. Babylon does not what you to do that. Why? Because it will break the spell. It will spell the end of its beguiling and brutalising power once and for all. But it’s true. The true Third Way is, even in the public square, to posit the possibility that there is an invisible realm. Don’t dial it down. Our task in word and deed is to announce the reality of the city that is coming down from heaven, the foundations of which will crush Babylon into the dust.

Let’s keep the Babylon motif, let’s just use it well. Oh, and I’ll listen to the rest of Max’s talk. It sounds worthwhile. Freedom For Faith should have those talks up on line some time soon.

Written by

There is no guarantee that Jesus will return in our desired timeframe. Yet we have no reason to be anxious, because even if the timeframe is not guaranteed, the outcome is! We don’t have to waste energy being anxious; we can put it to better use.

Stephen McAlpine – futureproof

Stay in the know

Receive content updates, new blog articles and upcoming events all to your inbox.