July 4, 2021

Australia: The Complacent Country

A dozen or so years ago I worked for an NFP organisation in the education sector that was helping young people at risk of school drop-out to re-engage with education and training. It was conference after conference; training seminar after training seminar.

I remember one of these conferences well. Not because it was particularly insightful, no more or less so than others, but because a causal occurrence at the event was a clarion reveal about the mindset of Australia and modern Australia in particular.

The presenter was about to conduct an onscreen poll and each person at each table was given a remote with which to cast their responses. So about 200 of us in the room, many of them leading educators, all ready to go through a vocational education poll.

But first the test question to see if the mechanics and electronics of the polling system worked. The test question was something like this:

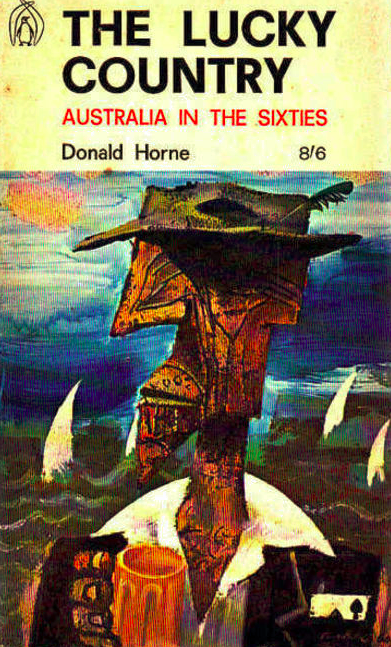

When Donald Horne labelled Australia the lucky country he meant that:

A) Australia is fortunate enough to have many advantages that other countries do not have.

B) Australia is a complacent country that has managed to avoid trouble more from good luck than from good management.

One person, that’s right, one person, in a room of 200 educators, pressed “B”. This is my humble brag moment. Everyone else in the room picked “A”. If I had been the presenter I would have stopped right there and changed my whole presentation – out of either despair or concern. If the educational leaders of our country were blithely unaware of the real problem in Australia, then what chance the young people they were trying to help? After all, eventually the luck will trickle down, right? Horne’s book is a searing indictment of a complacency that will lead us into trouble.

And note the subtitle, “Australia in the Sixties“. Most people in that room that day were born in the 60s, late fifties at earliest. “Lucky” was in the air we breathed on a hot summer morning, the water we swam in down at Cottesloe on a late summer evening.

Australia has been the complacent country, but as Horne pointed out, somewhere along the line luck has to run out, right? And it feels that that might be happening now, or at least being revealed for the complacency it is. The COVID response of the last week is case in point.

Last year we were feeling smug as a nation about how we were going with our lockdowns and our low death rate. There was a sense of superiority about our health system, our politicians, our lifestyles that would allow us to go into border closures while still having amazing holiday destinations to travel to. If we ever needed a vaccine it would surely come our way. Not for us the panicked, yet furtive line up. We’d get that vaccine when we darn well pleased. And we’d get the vaccine that we wanted when we wanted it. And if we didn’t? Dummy spit.

Now? We feel like the hermit kingdom that, among all the Western nations, is well behind the eight ball when it comes to figuring a way out of COVID. We watch from our lockdown TV sets as one of the creators of the Astrazeneca vaccine, Dame Sarah Gilbert, is given a standing ovation at a full Wimbledon tennis court with nary a social distancing in sight:

And what do we get? Hysteria. Hysteria and politicking of the most shameful kind, in which state leaders, seeking their own gain, and Chief Medical Officers, for goodness knows what reason, create alarm by grossly over-playing the risk of the vaccine. The same politicians and CMOs who, incidentally, were telling us how many thousands of people were likely to die in Australia last year of COVID.

The smugness has drained away pretty quickly, and within days the PM and the state leaders have been coming up with a plan to open the country up quick smart.

Now this is not a COVID blog rant. It’s simply saying that our COVID response – which began so well – fell into the complacency that Horne spoke of. We fell back onto the “lucky country” mantra, subliminally at least, because we believed that we’d done enough to stave off trouble, and we hadn’t.

Now everyone is lining up for the vaccine – or at least phoning up in an attempt to line up – now that we are in the lockdown loop. It’s a little like the fable of the man whose roof is leaking in winter, and when asked why he doesn’t fix it in summer, states that it never leaks when it doesn’t rain, so why should he? Well winter has arrived in Australia and our roof is leaking.

Lucky country? We’re not even the plucky country. Okay, call us plucky at the World Cup soccer, when we’re up against Brazil and England or even Croatia. But let’s save the term “plucky” for places like Croatia who, over the past 100 years have seen off Nazism, Communism, a Balkans bloodbath, and huge financial disparity, yet who soldier on, deeply religious and deeply scarred. If they ever get called “the lucky country” it will be because they have made their own luck.

And speaking of religious, nowhere is the complacency in Australia felt more than in terms of how people view religion, God, the afterlife, and attached to that, the spectre of death. We are, after all, the country that came up with the terms “She’ll be right”, and “No worries mate!”, because we think it will be right and we think there will be no worries. Even when there are.

As someone who has spent many years doing gospel work in Australia, including the dreaded door knocking, complacency is in the air we breathe. Sure there is a hostility in some quarters of Australian society towards Christianity in particular (I’ve even written a book that mentions that!), but the overwhelming feeling is “Meh!”. Most Australians just can’t be bothered about religion and see it as having zero relevance in their lives.

And why would they? It was the Negro-Spirituals that came up with lines such as “Swing low sweet chariot, coming for to carry me home.” They sang it in hope of a better place. A better place than this.

But Aussies don’t think there is a better place than this. This life is all there is. Even the now-discredited source of Mark Driscoll, when he was in Sydney years back yelling at Anglicans about how rubbish they were, declared, after seeing the sights of Sydney, that it’s no wonder so few Australians are Christian given that they have “heaven on a stick” right here.

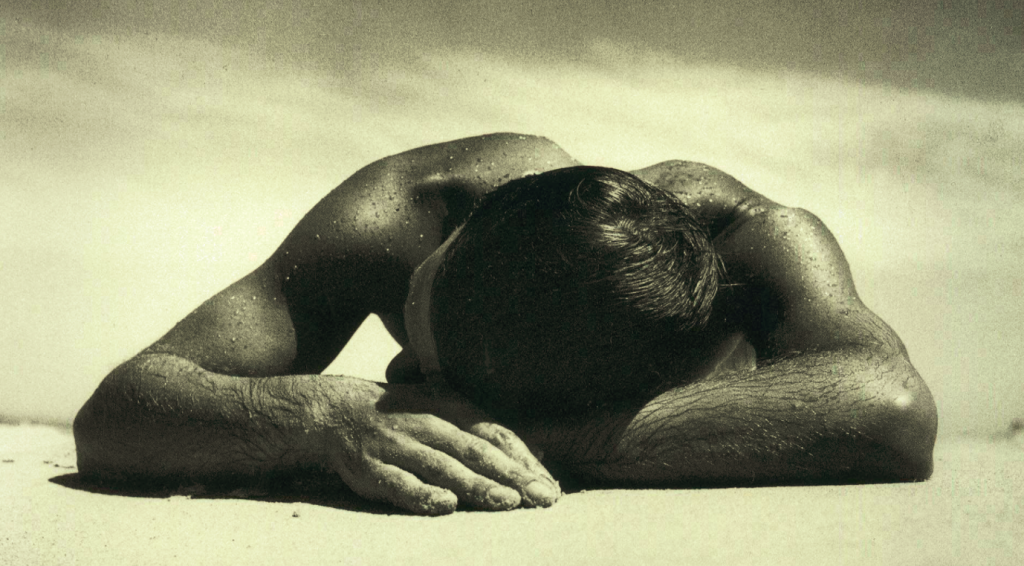

Indeed the image that sums up Australia to me most of all is this iconic photograph by Max Dupain, The Sunbaker:

I defy anyone who does not know when this photo was taken, to believe that it is almost 85 years old, and that the subject – and the photographer – are long since dead. It’s been sunbaking all the way through.

Yet even under all of this complacency on the surface, there lurks a terrifying sea beast, a great black shark, in the corner of our national eye. This terror – this quiet, implacable terror -, has been pointed at in the past by many others, not merely Christians.

Midnight Oil’s bleakly political Power and the Passion sums us up:

People, wasting away in paradise

Going backward, once in a while

Moving ahead, falling behind

What do you believe, what do you believe?

What do you believe is true

Nothing they say makes a difference this way

Nothing they say will do …

Sunburnt faces around, with skin so brown

Smiling zinc cream and crowds

Sundays the beach never a cloud

Breathing eucalypti, pushing panel vans

Stuff and munch junk food laughing at the truth …

The irony of course is that the loudest, most raucous renditions of that song that I have heard, have been down at the beachside car parks as parents slather their kids in sunscreen, and svelte young bodies sit atop the hoods of cars eyeing each other off.

Yet every now and then that shark breaks the surface. We live in a land with high suicide rates, a domestic violence level that is deeply troubling, and a porn addiction among our young men that is leaving them either violent towards women, or self-loathingly impotent within relationships in so many ways. COVID barely hit us with deaths, but the mental health tsunami has landed on our shores nonetheless.

Yet the good life is so alluring, even to Christians. It lulls us to sleep. So pastors will tell you of the effort it is to even get their congregations to turn up two or three weeks in a row.

The good life is more alluring than the great life of following Jesus, which on the surface can’t compete with what’s on offer. I mean, by the time the kids have done three sports and two music lessons and we’ve had the quarterly beach house visit Friday night to Sunday arvo, where’s the time? The bad life is extremely unlikely to sweep your kids away from Jesus, but the easy, but building, swell of the good life will sweep them off the rocks to be lost at sea by the time they are twenty.

The good life takes many guises. The Left will excoriate the Right for its blatant commitment to consumption. The Right will equally excoriate the Left for its blatant commitment to radical identity politics. But at the core of both is the deeper commitment still to radical expressive individualism, and the right, the entitlement, to choose our own course and map our own destiny. And if our course or map runs afoul of another’s, then we must re-narrate it to ensure that we come out looking squeaky clean.

Hence our apparent luck has not led to generosity. We are not the beggar given bread who must share it with others. A cursory glance at our economic aid shows that we are not generous.

Yet lest we become high and mighty about what the government is not doing for others, let me remind you of the words written on this blog by a Scottish friend of mine Diane, who ministered in an economically deprived area of Glasgow with her husband and children. They now live and minister in Perth, and Diane wrote these words recently:

GENEROSITY – As our son’s words exemplify, generosity was witnessed and experienced regularly in Glasgow. For instance, people turning up at our door, with their stuff, asking if our kids could use a bag of no longer-needed clothes or football boots (we were the family with a big car and a comfortable lifestyle). The annual sponsored walk we organised to help reduce the summer camp fees we took the local young people on, raised a hefty amount. And collections at school for food for the older folk at Christmas filled the stage in the assembly hall. Our youngest child recently came home from school stating that she had had discussions with her classmates about why they should donate to the Salvation Army appeal after many were showing a lack of sympathy to the poor and homeless in Perth. More resources but less empathy.

Her son summed it up with this question:

How come my friends in Glasgow were poor but they gave me their stuff, but my friends in Perth are rich and they sell me their stuff?

Simply put, we don’t get to outsource the generosity we don’t wish to show, to the government. Generosity springs from the grassroots of a culture and goes all the way up. If our government is not generous to those less fortunate, it is because neither are we.

What would it take to shake us from our complacency? For it will sure take something. I personally don’t hold to Horne’s more leftist politics, and it’s easy to see how his concern for the complacency could be weaponised by derision in the hands of others.

But a more centrist voice, demographer and social commentator, Bernard Salt, put it like this in 2017 when reviewing Horne’s take on Australia’s luck, particularly in relation to our defensive capabilities in an increasingly bellicose world:

Our prosperity is, however, a double-edged sword: it delivers a great lifestyle but also breeds a comatose people unhardened to the rigours required to maintain that prosperity. Peace and prosperity have come so easily, especially since Horne’s book was first published, that we have become lulled into a false sense of security.

2017. Just two years prior to a nasty little virus with a “19” attached to its name. Perhaps we have been lucky again. Perhaps COVID has been the shot across the bows that will finally make us wake up; finally make us shred that false sense of security , the complacency, all the way from the financial state of our banks to the spiritual state of our souls.

Written by

There is no guarantee that Jesus will return in our desired timeframe. Yet we have no reason to be anxious, because even if the timeframe is not guaranteed, the outcome is! We don’t have to waste energy being anxious; we can put it to better use.

Stephen McAlpine – futureproof

Stay in the know

Receive content updates, new blog articles and upcoming events all to your inbox.