October 5, 2018

Cheese Sandwiches, Picture Framing and Work

For decades my dad would get up in the morning, make a cheese sandwich – the regular boring cheese, not the classy stuff – get in his car, and drive off to work in some form of semi-skilled low paying manufacturing job in a factory on an industrial estate somewhere.

Every day the same type of job.

Every day the same cheese sandwich.

Two wives in that time.

Six sons.

Same job.

Same sandwich.

Dad lived half of those work years as a professing Christian, and half as not. Yet during neither phase did I ever recall him talking about his job as some sort of “vocation”; as a way to “glorify God”, or as “his passion”.

It was a job. Plain and simple.

Plain and simple and boring and repetitive.

Dad’s job was a means to the end of putting food on the table, clothes on our backs and, with a bit of luck, some money left over for fun or a cheap family holiday down south on the coast to escape the searing Perth summer heat.

There was no noble vision, no quest, no sense of call. Whether or not Wednesdays as “hump day” was a thing back then I am not sure.

What I am sure of was that by Wednesdays Dad would have been looking forward to Saturday morning when he could go into his shed and do some picture-framing, something he was passionate about.

His three areas of lack: business acumen, self-belief, and general education, meant his occasional plans to set up a framing business where his career and passion could collide never really took off.

Yet on Saturday mornings Dad was the master of his craft.

I can see him now: A cup of instant coffee on the side bench with some chocolate; mitring an angle with precision; running a tack through his thin hair before nailing it in; reruns of The Goon Show playing loudly on ABC radio; sun streaming through the window shimmering the dancing wood dust.

In that shed he was the master. He belonged here. This was his true vocation though it earned him little money. The pride in almost seamless joints. The look of satisfaction in a friend’s face at how Dad had gotten the moulding choice just right for that piece they’d bought overseas and which held such memories.

This weekend at our church I’m talking about work and the pendulum swing of our culture in which work risks becoming either our noble identity, or a necessary irritant.

And for people like my Dad there was no sense that he drew any identity whatsoever from his paid employment. It was just a job. Whether it irritated him or not I can’t tell either, so locked in was he to the process.

Much has been written about work and vocation from a theological perspective the past few decades, and there have been plenty of conferences about work, but as this article in Christianity Today points out, it’s not janitors and fast food workers – or even machinists – who frequent Christian conferences about work. And they’re not reading books on vocation either.

Once again evangelical Christianity has been great at targeting the middle class when it comes to dealing with the big issues of life. It’s no wonder our tribe is so middle class, or at least tends towards it.

After all we have the luxury of using the gospel to put checks and balances on just how much of our identity is tied up in our jobs. And the more we focus on the idolatry aspect of work, the more we call our fellow Christians not to idolise their jobs, the more distant we become in experience; and more irrelevant in message, to the working class among us.

Many low skilled, low paid workers, – many Christian workers – will never have the luxury of feeling angsty about putting too much meaning into their jobs, and risking their jobs becoming idols.

Nor the guilt of having too many other luxuries afforded educated or highly skilled trades workers: status in our jobs; financial rewards that allow us to let off steam in Venice instead of the casino, that sort of thing.

The Christianity Today article quotes the late Steve Jobs speaking, ironically about jobs, at Stanford University:

“You’ve got to find what you love. Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do.”

That’s a lot of weight for work to bear: “The only way to be truly satisfied“!

And I’m pretty sure when Jobs said “do..great work” his Stanford crowd, having drunk the middle class/elite Kool Aid that’s available on tap in those sorts of establishments, were not thinking of sweeping and polishing a floor so you can see your face it in, or of flipping a burger with such precision it lands on the burger bun pretty much without any overhang.

No. They were thinking of securing great vocations; employment that confirms the identity markers they value; that confirms the person they are crafting themselves to be; a title in a firm that is nationally and internationally renowned. And all the trappings that come with those status and identity markers.

And while Jobs was a Boomer whose idea of work was to blur the lines between work and play, my Gen-X crowd constantly sought the Holy Grail of combining what we were passionate about with an income stream; slowly and falteringly at first to be sure, but eventually with enough head of steam to become our main employ.

But somehow our generation fell through the gaps on this one. Here we are at fifty, with a couple of kids, a marriage, a larger-than-we’d-like mortgage, and a job that, if we squint right on certain days or in certain seasons of life; sort of fits that gilded picture on occasions.

Is that enough? Do we feel ripped off? If we heeded Jobs’ job advice I think we would be. Besides we’ve read enough cautionary tales about the way in which he train-wrecked relationships for the sake of his all-consuming work passion, that we’re not completely convinced.

All of this, as I said, is completely and utterly middle class in its thinking and its direction, the very crowd that would read a blog post like this.

Meanwhile the factory workers and shift workers and fast-food servers and aged-care workers get on with it, nip out for a smoko, check their phones, then get back to it before some middle management person calls them out for time wasting.

And they’re not reading this. They’re not going to conferences about how to integrate faith and work. And they’re probably not going to your middle class evangelical church either. If they’re Christian they’re in Pentecostal churches by and large.

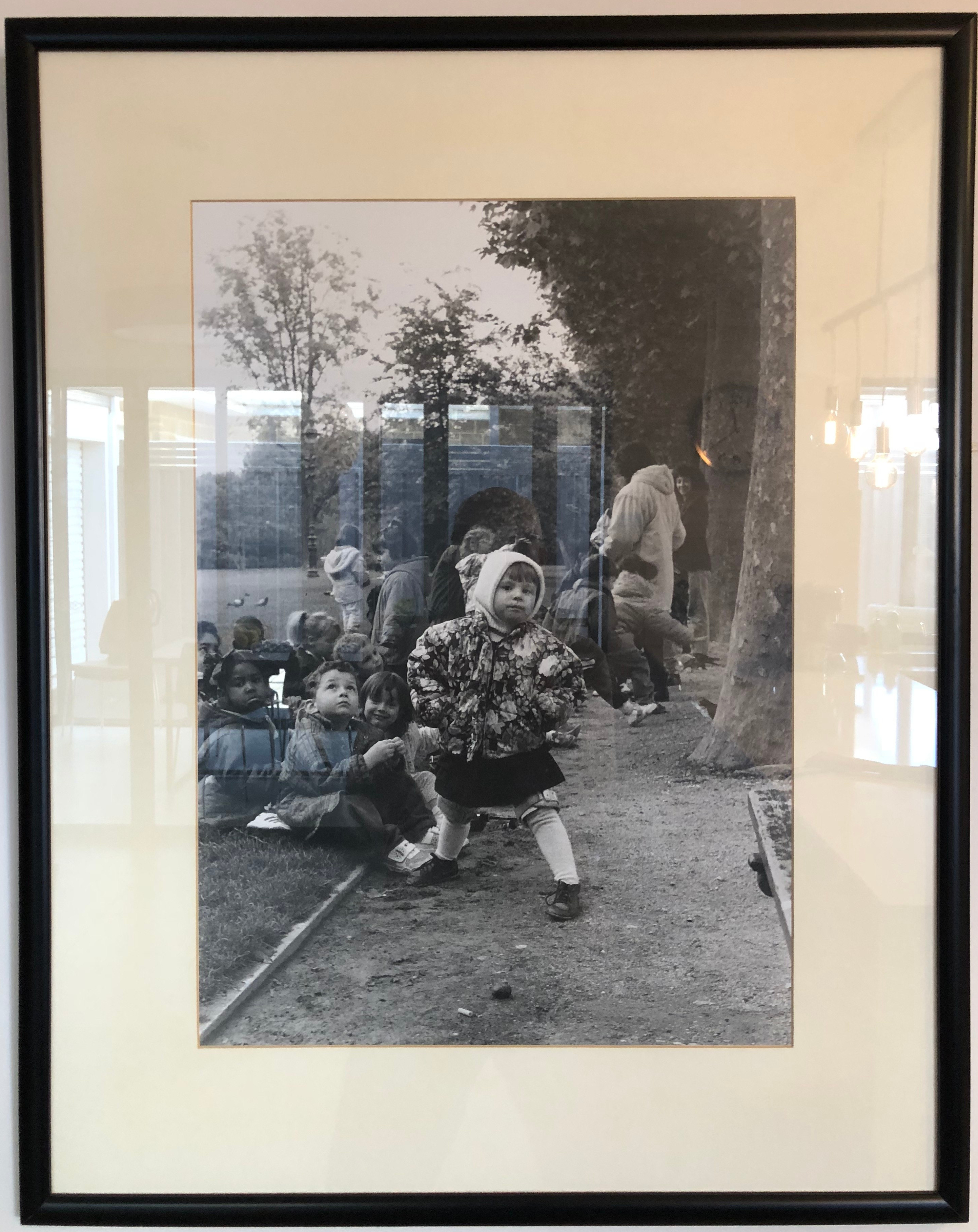

This picture below is of a photo I took in Paris back in the early 90s. I love it. It’s full of character (and characters if you look carefully). It’s right next to the Eiffel Tower. Who takes a picture of the Eiffel Tower? You can buy a postcard for that. I was more interested in what was going on underneath it.

And plenty of people commend me for that picture. (If you’re a great photographer don’t point out its flaws to me!). And apologies for the reflections, but it had to be reflective glass to give it the look it needed.

But for me there’s something more to it. I love the fact it was framed well by my Dad. The corners, the mounting board he used to give it that gallery feeling. The well-sealed backing that has stood the test of time. The double row of white cord that holds it up and is knotted so tightly and safely on its hooks. This thing is never for falling.

Oh, and Dad’s “McAlpine Art Frames” sticker on the back with a drawing of the Alps. The stickers he created and had printed because he had enough confidence in his craftsmanship to own up to his work. There’s a sense of completeness about this photo that I could not have brought to it by myself.

By trade I’m not a photographer, and Dad was a machinist in a factory all those years not a framer. But somehow, together, we captured something vocationally that is satisfying though it has made me no money. And I do love that I did it. And I do love that others admire it and explore it when they come to our house.

It’s not that we think too much of work. In a sense we think too little. We have cut off its edges, shaved it down to our understanding, corralled it into a status box, or a meaning box, or a compare-and-contrast box.

For this photo too is work. My work, Dad’s work, unpaid and uncelebrated perhaps, but a happy synthesis of a middle-class, well educated son, and a working class, poorly educated father doing something together that has stood the test of time.

And there’s just something redemptive about that.

Written by

There is no guarantee that Jesus will return in our desired timeframe. Yet we have no reason to be anxious, because even if the timeframe is not guaranteed, the outcome is! We don’t have to waste energy being anxious; we can put it to better use.

Stephen McAlpine – futureproof

Stay in the know

Receive content updates, new blog articles and upcoming events all to your inbox.