September 12, 2023

Hey Christians: Let’s All Give Two Cheers For Nominalism

Nominalism Schnominalism

Nominal Christianity has become the whipping boy for many a consultant/speaker on the Christian circuit these days. In fact it’s become a whole cottage industry.

To my shame, I have veered dangerously close to it myself in presentations. Especially when I say things like “It’s only when Christianity is believed and practiced by actual Christians and the rest of the world is a zombie apocalypse of post-Christian darkness that we’ll get traction again.” But I was reminded only last week in a gentle chide from a smart dude after a talk I’d given, that we should take care that we don’t get what we wish for.

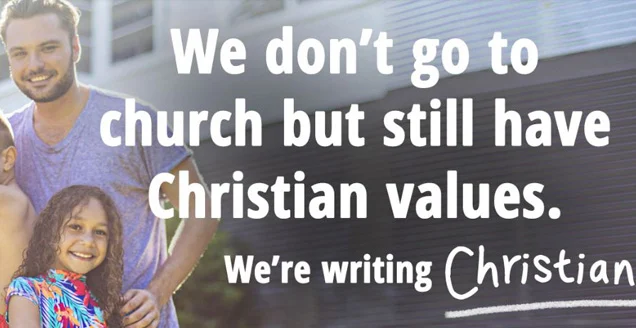

Fun fact: I’ve used the very picture posted above to describe the frustration I have with nominalism as a church pastor. This was the advertising campaign used during the 2016 census in Australia to counter the “Not Religious Any More?” secular campaign. Governments determine where monies should be spent off the back of census data, hence the interest in getting the downturn, or the uptick, on religious involvement.

But so often at conferences and the like, where every eager evangelist and church planter turns up, deriding that campaign everyone gives a rousing cheer. Three cheers.

Well not everybody. There are a bunch of people who can see the problem with the demise of nominalism. But only those people who have a keen eye for what it might mean for nominalism to fall off the table. Including those people, such as the secular historian Tom Holland, who is growing ever more wide-eyed at the post-Christian moral framework. Or the lack of moral framework as the case may be.

After all, as a historian, Holland knows that the pre-Christian world of Roman paganism wasn’t all amphoras of wine and toga parties. Not a bit of it. It was exposing baby girls on the hillside, the casual and expected sexual abuse of minors, slaves and assorted non-landed-gentry types. Brute power ruled the day. Consent? Sheesh, that old thing?

It’s easy to point out the obvious flaws of a Christianised culture in which the weightiness of God has been undermined culturally, even while the frameworks remain, and are tottering. I’ve felt that often enough. Christian church workers who get frustrated at the lack of cut through in their programs and offerings, and who start up a gospel program that no one turns up to, and that few of the church folk invite their friends to. The evangelists who are in despair over the the Christianised people who think they are good living types, and have Christianised values, but don’t want a bar of committing to Jesus.

Now such types are less prevalent than they once were, and are often ageing, but they still exist. And interestingly there’s a resurgence of, if not exactly nominalism, then a whole cohort in our culture (often those with young children about to go to school), who can see the cultural trainwreck, but don’t know why it’s happening, or what the solution is. Nominalism is here to stay, even if its less obviously “nominal”!

That’s explains the deep irony of secular parents signing their little ones up to Christian schools in droves for “the values”, if not for Jesus. They’ll begrudgingly admit to prayers and Bible in the classroom and the assemblies, Christmas and Easter celebrations etc, just as long as little Johnny still wants to be a lawyer when he grows up and not a missionary.

But don’t worry, pagan progressive governments are right onto this as well, with the keen sense of a wolf near a pasture. Even now many post-Christian governments in the West are making sure through legislation that Christian schools are gutted of even the nominal framework of Christianised ethics. After all, you can’t be too sure. This thing may rise again. That is, after all, part of Christianity’s allure.

Exangelical Glee

Christians love a good bit of self-flagellation around nominalism. At least that’s what I’m discovering. Put together a PowerPoint package that, although it doesn’t directly say it, attributes the ills of the world – well the Western world at least – to nominal Christianity and its vices, and it will fly. Excoriate the nominalism that has left the ghost of Christ among us culturally, but without the flesh and blood of a vibrant church. Prep that one up and spruik it and you’ll get a gig for sure.

You’ll get three cheers. Especially from those who are happy to align with the hard pagans of our post-Christian culture, and not merely attribute the ills of the church to nominal Christianity, but the ills of the culture itself to the very ideas that Christianity gave to the world. The air that we breathe, as Glen Scrivener would put it.

As if somehow, when we slough off the dogma and powerplays of a corrupt church and its strictures around sex, its insistence on family not the state as the locus of formation, and pesky start-of-life/end-of-life matters, then we’ll be liberated to enter what Australian Marxist academic Roz Ward of the trojan horse anti-bullying campaign, Safe Schools, calls a “more free and joyful world”. Them’s gospel words and ideas right there. That’s the Sexular Age and its message of hope – a post-Christian telos.

And yet there’s a veritable cottage industry built off the back of evangelicalism and its woes, often by ex-evangelicals (or exangelicals as the slang now goes). There’s a certain glee by those who have either junked orthodoxy, or indeed orthopraxy (along with their spouse of many years), to say that the ills of the world, and the refusal of the pagans to line up with the gospel, is simply, almost exclusively, down to bad churches. And bad churches of the past fifty or so years.

Yet we know from even a cursory glance at the New Testament that many of the churches were bad back then! From the Corinthians who liked to be sexy to Diotrophes who liked to be first (John 3). Even as all over the world “this gospel is growing and bearing fruit.” (Col 1:6). Yet that hasn’t stopped many a misguided exangelical from trying to form a Christian community that would struggle to admit Jesus to its own cohort because he wouldn’t be intense enough for their liking.

Or instead of not signing off on the Apostles’ Creed, he wasn’t able to sign off on the ten values that include a shared money bag (it was your idea in the first place Jesus!), or having dinner at each other’s houses three times a week. All the usual ninja-Christianity stuff.

Evangelism and Discipleship Frustration

Look, I get it. The biggest frustration I had at church were those who floated in and out. True nominals! Those who had a vestige of the faith and whose kids were increasingly bewildered by their parents flakiness. And who would grow up themselves to realise that the good life that their parents talked about was sans Jesus. And naturally, that’s the direction they headed in too.

Too often that means an evangelistic success story, one to truly celebrate, is the “I was the drag queen of Drag Queen Story Hour fame, but now I read The Jesus Story Book Bible to the five-year-olds from the ten o’clock service, and play my guitar while they sing ‘Ten, Nine, Eight, God is Great…” version of evangelistic success.

In other words, the really high hanging fruit. The fruity fruit. The fruit we talk about on social media. The fruit that was most definitely the fruit from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, rather than the rather obscure low-lying quince that hit me in the face walking through the orchard. Ain’t nobody got time for that fruit!

Well many people – many ministry people – do. They have a lot of time for that fruit. A lot of time for the fruit that doesn’t see itself as too good for the church, but sometimes too bad. Or if not too bad, too neutral to see why going would make any difference. Though they’re generally not the interest group for those who are the cultural movers and shakers of evangelicalism in our modern, progressive cities.

From where I sit there’s a lot of time and effort being put into figuring out how we can reach the LGBTQI community, and that’s not bad. But to be honest, that’s not the community that’s the hardest to reach with the gospel. Not by any standard. But it does seem to be the prized catch in some idealised world. A veritable podium finish evangelistically speaking.

But anyone celebrating the also-rans? Anyone tried to reach the average tradie bloke standing in the queue in front of you at the Thirsty Camel with a slab of beer over his shoulder? The bloke who’ll screech out of the carpark in his work ute, looking for a good weekend to drown out the monotony and hard yakka of concreting? The bloke whose rate of suicide, risk of violent death, and chances of ending up couch-surfing are so much higher than many other cohorts? Ministers generally only know the names of those blokes when they’re calling them up to fix the plumbing at the rectory.

The Case For Christian Nominalism

Almost perversely, nominalism has strengths that we need to lean in to. Not only does it provide some lower hanging fruit among people who don’t read Christian books – or perhaps any books -, but who might listen to a secular podcast that refuses to call good “evil” and evil “good”, and who see something disturbing about the sexualisation of our children, but it also provides the church with far more traction in the public square to proclaim a gospel that a post-Christian environment, or even many a pre-Christian environment does not.

The chilling clamp down on churches in the state of Victoria, under the guise of creating safety for sexual minorities is a case in point. But it’s not just all coming from one political direction.

As Ross Douthat of the New York Times observes in his book , “Bad Religion: How We Became A Nation of Heretics“, our cultural distaste for the Religious Right will pale in the face of our horror at the post-Religious Right. Reminding us that it’s not just the Left that despise Christianity. Of course students of 20th century history would know that. Pity there are so few such students left in our ahistorical age.

If you’re a Christian leader looking to evangelise, don’t celebrate the demise of nominal Christianity or seek to hasten it yourself, as if somehow that will give us a fresh slate. Churches and gospel faith die out completely in some parts of the world.

And have done. And are doing so. And the way they die out is by Christians dying out or being killed. I’m pretty sure the average Afghan Christian would give their back teeth for a nominal Christian state. Not that the likes of Stephen Wolfe, and his pernicious “The Case For Christian Nationalism” would offer Christian sanctuary to such disruptive Christian influences in his monocultural Christianised state.

And nominalism provides fertile soil for the common good in a way that post-nominalism will not. Post-nominalism will indeed call good “evil” and evil “good” and is currently doing so, and shouting down anyone who disagrees. That’s why my neighbours who struggle to understand the cultural mess begin conversations with “Look I’m not into church or anything, but something seems wrong with FILL IN THE BLANK.” Perhaps that’s your experience too.

Perhaps we need a book called “The Case For Christian Nominalism” that celebrates the humanity and gentleness gifted to the world by Jesus, rather than the clean, clear zealotry of the likes of Wolfe, which ironically mirrors that of his cultural enemies. Perhaps I might write it.

Nominalism won’t save people. But it might save us from some cultural wreckage and horrific state-sanctioned abuses that we can only now see coming. Why celebrate that? Why celebrate the cultural destruction that seeks to burn down the house? Nominalism might give us a foothold, in fact is giving us a foothold, among people who are confused and uncertain as to why the safety-brake seems to be missing from what they assumed were universal human values, but are only now discovering are part of the Christian program.

They’re the folk turning up at our Christian schools in droves, even as many an eager evangelist who despises nominalism is figuring out how to make their child their evangelist-by-proxy at the state primary school’s “Wear It Purple” day.

So I say, two cheers for nominalism. It won’t save people, but it might just save the conditions by which we can speak the gospel into their lives.

Written by

There is no guarantee that Jesus will return in our desired timeframe. Yet we have no reason to be anxious, because even if the timeframe is not guaranteed, the outcome is! We don’t have to waste energy being anxious; we can put it to better use.

Stephen McAlpine – futureproof

Stay in the know

Receive content updates, new blog articles and upcoming events all to your inbox.