November 27, 2017

Hey Nebuchadnezzar, the Zombies are Coming!

The question for politics today is how to build Babylon after Nebuchadnezzar has been dragged through the streets and hung at the gates.

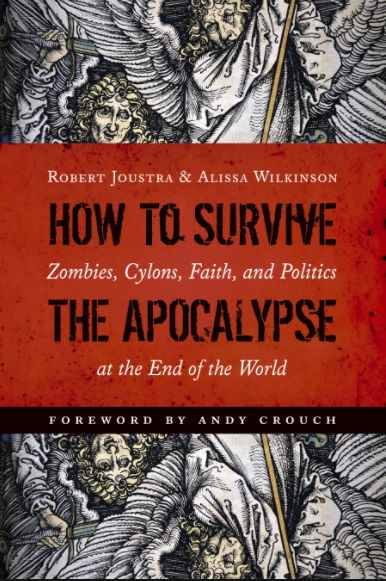

That’s a great observation made by the authors of How to Survive the Apocalypse: Zombies, Cylons, Faith, and Politics at the End of the World.

Leaving aside the incorrect use of the word “hung”, Allisa Wilkinson and Robert Joustra’s book is a cracking overview of the fractured nature of our political landscape, viewed through the eyes of the secular prophets, the creators of our most popular TV shows.

Shows such as Breaking Bad, Mad Men, Battlestar Galactica and, of course, The Walking Dead. The book, while populist, has a depth to it that belies its title. Some of you may be thinking “Here we go, another ‘hipster’ Christian take on all things cultural.”

Relax. This has depth. It engages with Charles Taylor, Jamie Smith, Alisdair McIntyre, Peter Leithart, et al. And the key question is the one posed right at the end of the book that I quote above.

For the authors’ contention is that while the political consensus in the capital “S” Secular age has fragmented into hostile tribalism, the unity that Nebuchadnezzar brought about by sheer brute power is actually not worth returning to.

Their question reveals their conviction that Babylon is the city we’re still tasked with helping to build, not the New Jerusalem, even while it attempts to strangle the life out of us.

Now you may be somewhat disappointed (devastated even) if you have been convinced that the job of Christians is to work hard to get the “old nation” back – whether that be Australia, the USA, or the UK. Or if you think that by sheer will power we can usher in God’s kingdom, or at least our approximation of it, whether that be conservative or liberal.

But frankly the Biblical evidence is that Daniel saw differently, indeed acted differently. God’s man saw the prosperity of Babylon as a worthwhile intermediary goal while waiting for the end of exile. Today’s Babylon mistakenly assumes that the goal of human flourishing is human flourishing. Like Daniel, we too can take what has become an idol and turn it towards its true goal – the glory of God.

Now that’s not to say we are completely in a Babylon state (yes you heard me say that), because as Wilkinson and Joustra point out, the glue that held the system together is no longer there. Babylon is fractious, but also fractured. And the king – tyrant though he was -, protected Daniel from those angling for his downfall, if for no other reason than Daniel’s interests so often coincided with his.

But when that has gone? When the strongman who kept the peace is deposed, what then? Are we merely left with an increasing post-Tito balkanisation in which the factions tear each other apart? Can we rebuild any consensus? Should we even try?

Wilkinson and Joustra believe we should, but caution against what they call the first obstacle to rebuilding; a common and ugly nostalgia. They state:

Nebuchadnezzar was never the king of kings he pretended to be, and most of us knew the story was going to end this way. Pining for the halcyon days of his reign in Babylon is both bizarre and vaguely masochistic. The relative optionality that a Secular age makes possible is both unsettling and dangerous, but it is wrong to say it is worse, or even more dangerous, than the hegemony that came before… We have a kind of radical pluralism – or maybe more to the point – we are now aware of a kind of radical pluralism that has not been true at a mass, cultural level before in human history. It makes us anxious about the bad choices that are always ready to be grabbed. It also makes us more responsible than ever when we grab them.

They go on to argue that this radical pluralism makes our systems and institutions “more important than ever.”

In one sense we all agree with that, otherwise the competing factions would not be fighting for control of these systems and institutions at the level of hostility they currently are. But in their competing desire to be undisputed champion, the warring parties should heed this word of caution:

…there is probably no perfect arrangement of political and social institutions that will satisfy a basic breakdown in moral and cultural consensus. We depend on virtues that laws cannot uphold, and values that markets cannot sell.

There’s the tension right there. With consensus gone we’re in a free fall ( a little like the opening credits to Mad Men) until somehow we manage to right ourselves – if indeed we ever do, given we no longer know which way is up. No future, humanly speaking, is assured. The idealistic socialist sounds as twee as the Christian reconstructionist when they speak of their utopia.

That misguided desire for nostalgia is partly the reason why so many in the recent same sex marriage plebiscite who were campaigning for No, assumed that this could be another Brexit or Trump. That somehow there was a great silent mass of people who – like those who wanted to make America great again, or wanted to put the “Great” back in to Great Britain- , would haul a No vote over the line and upset the elites.

What they never counted on was the growing “marriage” between political/business conservatism and progressive morality – that radical pluralism Wilkinson and Joustra speak of.

Trumpeters and Brexiteers may want to see their countries great, but they also reserve the right to make themselves great any which way they feel. It’s an age of deep individualism and deep individualists voted for the status quo. It just happened that the definition of marriage had to change to maintain it.

So what do we have now? The anxiety of many who predicted something like a 51-49 per cent stalemate. All too late they have realised that their local MP, who champions all small business and fiscal responsibility in the community newspaper, also wants to marry his gay partner.

And Christian leaders who were hoping for – perhaps expecting – that sort of outcome in line with Trump and Brexit are pretty dead in the water as far as being able to lead their people faithfully through hard cultural change is concerned. It’s all cyclone fences, shotguns and bulk orders of beans and spam for them now. And anger. Lots of anger.

That is not to say I am happy about the way in which the religious freedom debate is being framed – or even ignored in Australia. I can hardly countenance a Premier – such as here in WA -, who cannot even see how sexual ethics may play a part in how a Christian school chooses its staff.

This blindness demonstrates that the average secular thinker has no understanding of the religious mindset or practice within community. Which is a pity really, since secularism is a minority position on the planet, and increasingly so because wherever it increases in influence the population shrinks. The goldfish looks big in the fishbowl, not so much in the pond.

Which is a reminder to avoid that common and ugly nostalgia Wilkinson and Joustra speak of. There is no going back. Cultural hegemony has had to give way to cultural negotiation. And that will increasingly be the case for all sides.

Sensible heads are needed. Going through the stages of grief is a long and tiring process and can be avoided if we instead, do what these two authors suggest, and “refocus the work of politics to finding common cause; locating, building and maintaining overlapping consensus among our many and multiple modernities.”

In other words, everyone is on training wheels, even the secular progressives. Swing the pendulum too hard in one direction and the law of physics will have its way. Those who confidently think the course of history is settled are likely to be run over by it when it lurches. And there’s certainly no excuse for what almost seems like rage from some sections of the Christian community in the face of the seemingly interminable anti-Christian push. As Psalm 2 reminds us, leave it to the pagan nations to rage, we have a sovereign God.

No one is an expert on this where we are headed, nor is one particular position guaranteed victory. For a while there will be angular and hostile discussions. For a while we may end up fenced off from each other, destined for a time to keep one eye open. Indeed that could well be the time for the church to explore a robust Benedict Option, ready to return when the breezy, teenage optimism of the liberal agenda gets its fingers bitten.

The zombies may well be coming, but, as The Walking Dead is wont to remind us, they’re never the ones to fear. Somewhere along the line we’ll have to forge new alliances with those who, even now, we have never even sat across the table from, never mind shared a meal with.

Written by

There is no guarantee that Jesus will return in our desired timeframe. Yet we have no reason to be anxious, because even if the timeframe is not guaranteed, the outcome is! We don’t have to waste energy being anxious; we can put it to better use.

Stephen McAlpine – futureproof

Stay in the know

Receive content updates, new blog articles and upcoming events all to your inbox.