March 21, 2017

Jumping The Dead Shark

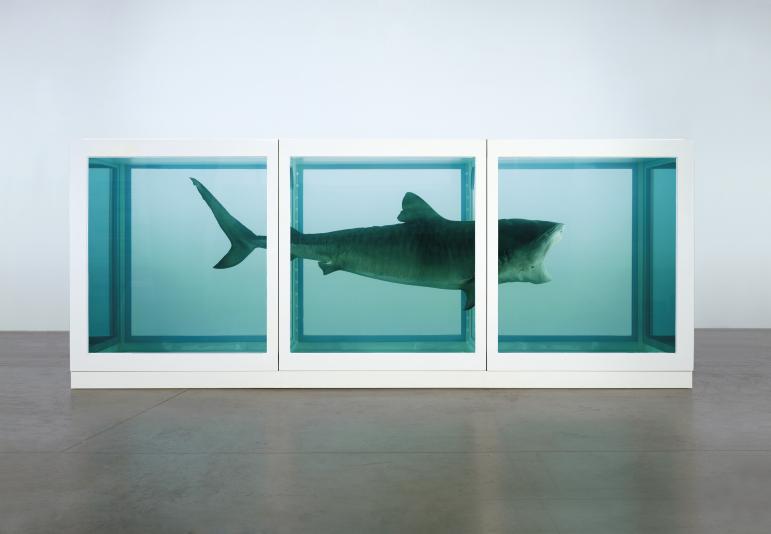

Two of the great works of art on death don’t simply posit the inevitability of death, but go deeper. The sheer mental magnitude of considering one’s own demise is summed up brilliantly in Damien Hirst’s memorable shark suspended in formaldehyde; The Physical Impossibility of Death in The Mind of Someone Living.

To observe what happens when death visits someone or something else , despite our shock or grief, does not prepare us for our own physical end. We stare and we stare at the dead, but cannot put ourselves in its place.

The second great piece is perhaps, for me, the greatest piece of art about death; the novella by Leo Tolstoy, The Death of Ivan Ilyich. What makes Tolstoy’s piece great, indeed what sets it apart, is how the news of the death of the eponymous Ivan strikes his friends not with terror, or existential angst, but with a self-congratulatory complacency. Tolstoy could mine the rich seams of a human mind like no other:

Besides considerations as to the possible transfers and promotions likely to result from Ivan Ilyich’s death, the mere fact of the death of a near acquaintance aroused, as usual, in all who heard of it the complacent feeling that, “it is he who is dead and not I.” Each one thought or felt, “Well, he’s dead but I’m alive!”

Hirst’s work, although confronting because it occupies immense physical space, is not nearly as confronting as Tolstoy’s, which occupies immense spiritual space, a product no doubt of The Russian’s own less than orthodox spirituality.

Simply put Tolstoy doesn’t shock us with the immediacy of death; that would be too obvious. He shocks us with the serene lack of concern that we exhibit towards deaths that are close, but not too close; an altogether more subterranean affair.

This is something I have observed as I have conducted funerals. How those at the back of the funeral cortege are talking football and white goods, whilst those at the front are sombre and silent.

Lest you think this is only about the complacency of our own deaths, let me widen the scope of this trend. This same complacency at the death of the other is exhibited par excellence in the ongoing cultural narrative in the late modern West.

It is all too easy to pooh-pooh the idea of a culture in collapse and facing death, and to scorn those, especially within the Christian framework, that all we are letting go of is the gangrenous dogmas that have bound us to the dead past. Yet it’s entirely possible, and in my view, probable, that those who predict an imminent cultural collapse, who are declared wrong ad nauseum, will suddenly be right about it when it happens. Yet, and this is the supreme irony, none who scorn now would admit to when it does.

Why? For, ironically, the scorn that emanates from those who see this current cultural collapse as not merely not collapse, but a kind of progressive maturity and growth, have already witnessed the swift and sudden demise of the old unreconstructed Marxism to which they had first hitched their philosophical wagon. Yet their confidence remains undented in their new cultural playground – a triumph of hope over experience if ever there were one.

The breezy optimism to almost the very last day that the wheels would not fall off the Marxist experiment was counter-balanced by a steely resolve that the West’s wheels were just about off the rims themselves. Indeed East Germany’s second to last leader, Erich Honecker, said that the Berlin Wall would last another hundred years just weeks before it fell.

When the wheels – inevitably from this side of history – did fall off and the wall fell down, the neo-Marxism that arose in its place, rather than shaken in confidence, simply transferred its hopes and dreams parasitically to a new host; the West.

But no lessons were learned in the process. No philosophical humility. No mea culpa. Not even a we wuz wrong! No. The neo-Marxist progressive agenda is supremely confident that it can shape a new secular eschatology from the very cultural frame whose demise it predicted not a few decades before, and continues to undermine.

Yet cultures don’t decline slowly, they collapse, and often quite quickly under their own accumulated detritus. History has proven it, and Scripture observes it. The apocalyptic chapters of Daniel reveal the series of cultures and kingdoms thrown up by the churning sea of history and what we see is the sudden rise and then equally sudden collapse of cultures. Hence in Daniel 8 we get this pithy, vivid insight into a swift cultural demise viewed through the lens of apocalyptic imagery:

5 As I was considering, behold, a male goat came from the west across the face of the whole earth, without touching the ground. And the goat had a conspicuous horn between his eyes.6 He came to the ram with the two horns, which I had seen standing on the bank of the canal, and he ran at him in his powerful wrath. 7 I saw him come close to the ram, and he was enraged against him and struck the ram and broke his two horns. And the ram had no power to stand before him, but he cast him down to the ground and trampled on him. And there was no one who could rescue the ram from his power. 8 Then the goat became exceedingly great, but when he was strong, the great horn was broken, and instead of it there came up four conspicuous horns toward the four winds of heaven.

Note those words: “but when he was strong, the great horn was broken.” Not when he was weak or bloated or distracted, but when he was strong. The clear picture is that something external, something beyond the ken of a materialist worldview, did the act of breaking that cultural horn at the perceived height of its strength, Biblical eschatology breeds a cultural humility that materialist eschatologies do not possess.

The Western cultural context is on far shakier ground than that goat, and that without any perceived external intervention. And that ground is shaky because you cannot keep chipping away at the foundations without the structural integrity failing eventually.

Yet, damningly, the same optimism of the neo-Marxist also inhabits some within the Christian sphere when it comes to how the future is onward and upward. The new ethical frameworks, built upon radical personal autonomy, are well positioned to take us to a new future, apparently.

Hence one commentator, in relation to the new ethics sweeping the West, stated that with our Western foundation of both the Reformation and the Enlightenment, universal human rights compel us to permit equality in ways we could only have imagined in the past. He quotes, approvingly, the well known start of the US Declaration of Independence:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Yet the Western secular frame of the last thirty years has not simply challenged the huge religious and philosophical assumptions contained within this statement, but positively taken the sledgehammer to them. What about any of these truth is self-evident in the new secular frame? They are not, neither can they be. Our forebears failed to put into practice what they claimed to be true. For that they must take the blame. Yet our problem is the opposite: we fail to believe what we claim we can put into practice. It cannot happen, not for long at least.

An example from another culture will show how precarious the ground is upon which we stand. In the past two months Christian aid agency Compassion has been forced to give up its work in India, where it was paying to feed and educate hundreds of thousands of children, moving them out of poverty – and here’s the crunchy bit -, “in Jesus’ name”. Compassion has been committed to maintaining its distinct Jesus focus, and works in situ alongside local churches in its mission, even when other aid agencies saw it as expedient to dump “the Jesus bit”.

A Compassion worker said to me in light of the sanctions that the great pity is that the Indian nation possesses no philosophical or religious framework that would encourage it, or indeed shame it, to take over such critical and needy work itself. Why take children out of need and poverty when both the caste system and the Hindu belief in reincarnation positively resist it? There is nothing universal or self-evident about the “truths” we are so confidently assessing, and the global population that no longer believes these truths – or never did in the first place – is demographically waxing even as we wane.

Now no such framework in the West either. We cannot argue compellingly and universally from a “Creator/creature” framework in the public square. That much has been tested recently and proven to be so here in Australia and beyond.

Those who would call for unalienable rights, but reject the alien means by which these rights are rendered unalienable, are merely self-destructive squatters, living in a house whose foundations they have dug up for the purely aesthetic purpose of building an impressive idol in the backyard.

The structure cannot stand despite all the colour, noise and affirmations. Mark Sayers, in his book, Disappearing Church, labels this “the beautiful apocalypse”; a glittering facade behind which the grimacing skull of death is concealed. To extend my Compassion staff member’s analysis to our own setting, we now possesses no philosophical or religious framework that would encourage us to view human rights as unalienable, we just don’t realise it yet.

Well, it’s not total ignorance. Truth pokes through the collective conscious from time to time. Why else are cultural gatekeepers so keen to hold the keys of what defines personhood so tightly? If a Creator is no longer there to endow such rights, then someone else has the privilege and responsibility to confer those goodies, and to decide who gets which goodies, or whether they get any at all.

Whether it’s the impossibility of considering our full blown cultural collapse, or merely the settled complacency that what has happened to others has not, cannot, happen to us, we seem incapable of grasping just how far our culture has shifted from its foundations.

And perhaps, just like Bruce Willis’s psychoanalyst character, Dr Malcolm Crowe, in the only good M Night Shyamalan movie ever made, The Sixth Sense, it could be that our Western culture has already died and we just haven’t realised it yet.

Written by

There is no guarantee that Jesus will return in our desired timeframe. Yet we have no reason to be anxious, because even if the timeframe is not guaranteed, the outcome is! We don’t have to waste energy being anxious; we can put it to better use.

Stephen McAlpine – futureproof

Stay in the know

Receive content updates, new blog articles and upcoming events all to your inbox.