February 25, 2019

Making Bricks For Evangelical Pharaohs

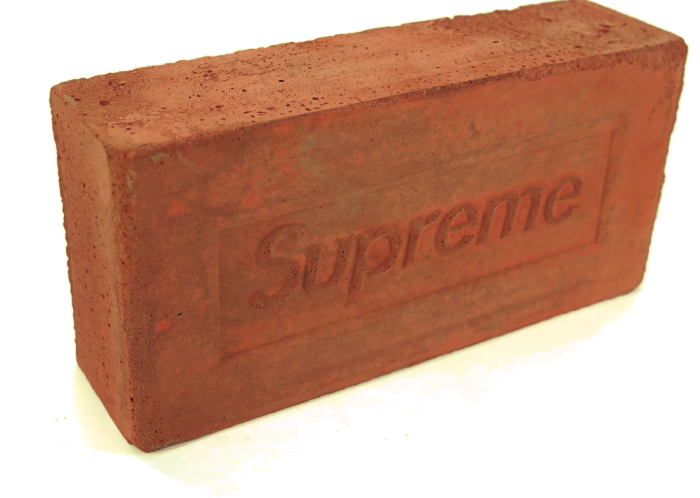

I worry that an awful lot of modern day ministry is about making bricks for evangelical pharaohs. Whether those pharaohs are actual people, or whether they are systems and philosophies of ministry that have been put in place, doesn’t matter all that much; making bricks is the paradigm of much modern ministry. And it’s leaving a trail of exhausted people in its wake.

There’s too much evangelical ministry based on the brick making principles of Egypt, and by that I mean a relentlessness to its demands on its people that is a stranger to the idea of rest. Let me explain.

I’ve just read Walter Brueggemann’s Sabbath as Resistance, as good a book as any to read while you are on sabbatical. Brueggemann unpacks Israel’s flight from Egypt to freedom on the verge of the Promised Land. And he notes that although Pharaoh did not get to Mt Sinai with Israel, the imprint he left on God’s people did. And that is why the prelude to the Decalogue is there: to remind God’s people what they are coming from before pointing out what they are coming to:

I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery. Exodus 20:2

God’s people have been making bricks. And more bricks. And yet more bricks. The demand for bricks from Pharaoh has been insatiable. How many bricks? Just more. A quota that is presented initially as achievable, primarily because it is presented as a quota, morphs to the point that somehow that quota is never quite enough.

There is never an end to the brick making. Pharaoh sits literally at the top of the pyramid, the typical apex leader, whose agenda is for all others to serve, and whose narrative to the people further down the pyramid that in reality we’re all in this together serving the gods.

Brueggemann says this:

It is clear that in this system there can be no Sabbath rest. There is no rest for Pharaoh in his supervisory capacity … Consequently there can be no rest for Pharaohs supervisors or taskmasters; and of course there can be no rest for the slaves who must satisfy the taskmasters in order to meet Pharaoh’s demanding quotas.

Brueggemann’s conclusion is clear:

It requires no imagination to see that the exodus memory and consequently the Sinai commandments are performed in a “no Sabbath” environment.

Sabbath is plonked in the centre of the Commandments precisely because everything else is to radiate out from that idea. Brueggemann notes that the commands that follow in the rest of Exodus are a “commitment to relationship (covenant), rather than commodity (bricks)”. You could say that Sabbath is there to launder out of God’s people the performance driven fear that enough bricks have not been made, and instead plant in them the faith that God is bringing them into a land with houses that they have not built. That’s the gospel right there!

Yet here’s my concern. Just like Israel, God’s people today are struggling with that concept. There’s a relentless push for progress that we are being swept up in, and in an era of what I call “Big Eva” – the large evangelical ministry juggernaut replete with conferences after conference, ministry tool after ministry tool, leadership summit after leadership summit, technique after technique, there seems very little commitment to true rest. Apex leaders atop ministry pyramids are pushing God’s people with a sanctified version of brick making that has no end in sight.

And what does that look like? It looks like no rest. It looks like aping the pyramid/apex leadership and structures of the Pharaohs. And in a land of secular Pharaohs, the easiest thing to do is to mimic them, and create sanctified versions of the same thing.

My concern is that too many church leaders pooh-pooh the busyness of their people and constantly call them out of it, but merely to call them to a sanctified version of that busyness that, at its heart, is simply another version of brick making: “Hey you’re way too busy over there in your office/work/home, how about you come and be way too busy over here instead, for the right thing.”

After all, Israel may have left Pharaoh behind, but they were about to enter a land where Sabbath was also unknown. They were going to have to go against the grain to show what true rest looked like. The default would be to fall into a Promised Land version of being too busy.

As I survey the increasing wreckage of “Big Eva” across the Western world, with the scandals and burnouts, the sexual and spiritual abuses, there is a clear pattern -rest – sabbath rest – is glaringly absent. Left behind the now disgraced pharaohs is a trail of burned churches and exhausted sheep, who were told they were doing God’s work, when all too often they were making bricks for a ministry Pharoah.

When it comes to keeping an actual Sabbath I think western evangelicals have been particularly prideful. The stated aim of junking the Sabbath was that we were ridding ourselves of old and unnecessary legalism. But think about it. At the very same time the secular frame was ramping up the means of production to an exhausting level that would never top out, and one that ridiculed the need for a break, we fell into line with it.

Its often been pointed out that the progressive, liberal arm of the church has been a day late and a dollar short with the sexual revolution, always falling into line with the culture on sex. But as Brueggemann’s title suggests, good, solid evangelicalism has failed to resist the progressive narrative in terms of what we tell ourselves we are capable of achieving, if we just try/give/serve that little bit more. We have junked the Sabbath at precisely the time in modern history that we should have doubled down on it.

We have prided ourselves as modern progressive evangelicals to have outgrown the need to restrict ourselves with Sabbath keeping, never realising that as Jesus said, the Sabbath was made for us and not the other way around. But absent as rest from our labours, our need to self justify all of the time.

The very fact that Jesus is our rest, our true Sabbath, should have forced us to ask ourselves why we still feel so driven that even our church gatherings feel like hard work, and that our church ministries and philosophies feel like time and energy suckers to most people.

The loss of an actual Sabbath among most proponents of “Big Eva” simply points to the absence of what Sabbath points to – rest from our labours and an unerring trust that God has got this. There is a clear pattern of sanctified brick making in which “Big Eva” apes the progressive narrative of late modernity, rather than, like Israel was called to, running counter to it. It’s just as frantic and just as destructive.

In the New Testament we are not called to make bricks. We are not called to build. In fact we are called stones, “living stones”, who are to come to the Chief Cornerstone, the one rejected by Israel’s leaders, and we are to let ourselves be built up into Christ. None of this is to say that there is not gospel work to be done. Not at all. But from how I see it, we’re a long way from laziness. We’re a long way from allowing ourselves to be shaped and formed by Christ and his Sabbath.

“Big Eva” is starting to creak under the sustained pressure of a hostile culture and an incessant demand for progress and targets. In many places that pressure has caused it to crack and fall. The time is ripe for us to reassess whether we’ve simply fallen for an interminable demand for bricks by evangelical pharaohs, because as I survey the scene it sure feels that is where we are at.

Next time: Why the Promised Land worked so well and the dangers that presented to newly freed slaves.

Written by

There is no guarantee that Jesus will return in our desired timeframe. Yet we have no reason to be anxious, because even if the timeframe is not guaranteed, the outcome is! We don’t have to waste energy being anxious; we can put it to better use.

Stephen McAlpine – futureproof

Stay in the know

Receive content updates, new blog articles and upcoming events all to your inbox.