November 13, 2018

Nationalism Is The Worst Thing Ever. Along With Globalism

Nationalism is pretty much the whipping boy of international progressive politics these days.

And not without some reason. It is after all, 100 years this past Sunday, since the guns fell silent, ending the slaughter of the Great War that decimated the cream of Europe’s youth.

French President, Emmanuel Macron, summed up the chastened feelings of many when he said these words commemorating Armistice Day:

Patriotism is the exact opposite of nationalism. Nationalism is its betrayal.

And the picture above, which looks like Emmanuel asking German Chancellor Angela Merkel for her hand in marriage, sums up where the future lies – beyond borders.

Leaving aside that many people do not know the difference between patriotism and nationalism – which for others are twin evils anyway -, the takeaway from this is that nationalism is a scourge that can only lead to death and war and tyranny. And we have to do something different.

So on the flip-side, and increasingly seen as the only side among the ruling elite of the Western world, globalism is viewed as the saviour of the planet. And the rising nationalism we’re experiencing around the world is putting that salvation at risk.

If we thought more globally and less nationally, so the story goes, then things would work out better. We would co-operate more and we would get more done together. And there would be a better chance at peace.

And on the surface that seems to work, especially if you live in New York or London, drink single origin coffee and have an information, high tech or financial career. If you’re that person, then nationalism is matched only by suburbia in terms of subject matters that make you recoil.

But Catholic writer and editor of journal First Things, R R Reno, urges a handbrake on this helter-skelter surge towards globalism, a surge that is swallowing up a large proportion of progressive Christianity also. He points out that globalism’s proponents unashamedly push its mythical qualities; qualities that blind adherents to its ills.

Globalization has a unifying dimension, which we rightly applaud. At the same time, though, globalization is associated with economic and cultural changes that are dissolving inherited forms of solidarity—the nation foremost, but local communities, as well, and even the family. This dissolution encourages an atomistic individualism, which in turn makes all of us more vulnerable to domination and control.

It’s easy to decry nationalism when you’re sitting in a city drinking good coffee, surrounding by the high tech stuff that came your way so cheaply because of globalism. And it’s even easy to do that as a good missional church planter in that city, without given a second thought to why you’re so attached to the globalism myth.

And it’s probably why you’re a church planter in New York or Portland and not in some god-forsaken, steel-industry forsaken town somewhere outside of Michigan. Have a read of A J Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy if you want to see what an atomised culture stripped of all jobs and hope, and mediating institutions looks like.

So here’s the caution, and it’s one Reno points out in quoting from an essay in Foreign Affairs entitled “The Fusion of Civilisations: The Case for Global Optimism” which “outlines a vision for a more globalized, peaceful, and prosperous future—in which nations become less significant.”

Reno observes:

Today’s emphasis on multiculturalism and “diversity” participates in this vision of the future, one in which differences are overcome and borders are irrelevant. It’s a species of utopianism, to be sure, but it has a powerful grip on the moral imagination of the West.

And it’s there that I think the problem lies. Not so much in the down to earth workaday work of politics, but in the ethereal world of our collective moral imaginations. It’s the problem of optimistic over-reach, and I’ve noticed it’s a problem that some versions of progressive Christianity have lapped up rather unsuspectingly.

Let me explain.

If you visit the symbols of nationalism in a particular country, the national Parliament for example, take a walk around the outside of the building. Notice the national symbols, the national statements. They are symbols and statements of history. History defines the nation. There is no doubt it is also myth-making in what it is doing, but it is a bounded myth, and one bounded by history.

But when you visit the parthenon of globalism, that international parliament of the United Nations in New York? The myth on offer is not derived from history or, importantly, bounded by it, but projected from the future – and not just any future, an eschatological one.

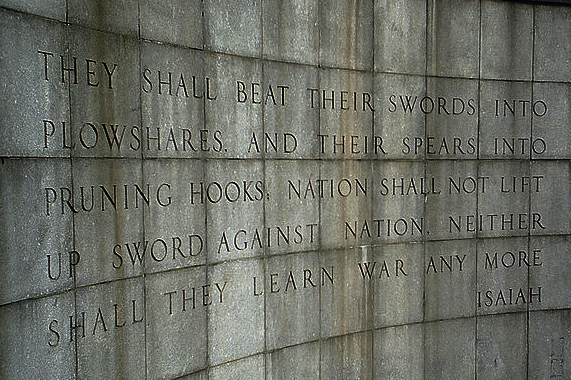

For what do we see outside the UN building? These words:

The words of Isaiah the prophet. Good words indeed. But words devoid of, indeed stripped of, their Messianic, eschatological context. Here is hope for peace indeed. But without the King of Peace himself. The myth has been ripped from its transcendent hope and given an entirely new gloss altogether. And as we have observed before, when the transcendent disappears in a culture, everything that is non-transcendent moves one floor up to fill the space it once occupied.

Reno goes on to say this of the curious, but breezy optimism of globalism:

In this view, national interest is an impediment to progress….By my reading of the signs of the times, the dangers of dissolved solidarity in the West are far more dire than our present upsurges of ethnocentrism and nationalism. It is atomized societies that are susceptible to demagogues—not societies that enjoy strong social bonds and organic communal solidarity.

Now none of this is to sign up to the fundamentalist crazies who view the head of the UN as the anti-Christ or some such, it’s merely to point out that progress is an astonishingly gripping myth, while even at the same time the things it purports to champion, are being destroyed. And we must be careful as Christians not to buy into the myth hook, line and sinker.

For there is a strand of progressive thinking in Christianity which implies that our role in kingdom building is such that the Parousia will be less a case of Jesus bursting through the clouds and destroying his enemies with the breath of his coming, and more a case of him slipping into the driver’s seat, taking the steering wheel from our hands and saying “Thanks, I’ve got it from here.”

That is simply a Christian capitulation to the utopian myth-making that globalism offer us. And since it’s a future-oriented utopian myth, globalism will, by its very nature, refuse the possibility of either a critical assessment of its own weaknesses, or – more worryingly – reject any limit to its over-reach. After all, without any external end point, such as the Parousia, who is to say when the myth has been consummated?

Of course, when it boils down to it, nationalism and globalism both have the same fatal flaw – they are salvation stories without a saviour. And without a saviour they can, when combined, occasionally create a living hell.

And I close with a chilling example of that hell, the Srebenica Massacre in 1995. If you’ve never seen the documentary of Dutch UN troops, then it’s a numbing watch.

I used the word “hell” advisedly too, as former US Ambassador to the UN, Samantha Power wrote a book called A Problem from Hell, about the incident.

The Dutch were charged with protecting local Muslims in Srebenica during the break up of Yugoslavia, as nationalistic Serbian murderers rounded up the Muslim men and killed them.

Unfortunately, the global powers had decided – specifically the UK, USA and France, but backed by many others – that for their own good global reasons, the promised airstrikes to beat back the Serbs should not go ahead.

The sheer anguish in the Dutch UN troops, charged with keeping “the peace” and therefore not allowed to initiate armed resistance, is harrowing to watch.

They were forced to hand over more than 8000 Muslim men who had fled to the safety of the UN compound. Powerless to do anything about it, the Dutch watch on as the Serbian thugs march them off into the local woods to be slaughtered.

In the documentary Dutch troop carriers are stopped and searched by armed thugs and fearful crying boys are hauled out and dragged off to their death, and no one does anything about it.

Of course this is not the fault of globalism. It is the fault of extreme nationalism, no doubt about that. But when it came to the acid test, globalism sat by and watched.

Both nationalism and globalism will lead us down blind alleys if we refuse, or sideline, the One whose actions in history have set the agenda for the future.

Emmanuel Macron may be the darling of the globalism set, but it’s another Emmanuel – God with us – who is our Saviour.

Written by

There is no guarantee that Jesus will return in our desired timeframe. Yet we have no reason to be anxious, because even if the timeframe is not guaranteed, the outcome is! We don’t have to waste energy being anxious; we can put it to better use.

Stephen McAlpine – futureproof

Stay in the know

Receive content updates, new blog articles and upcoming events all to your inbox.