January 8, 2019

Responding to Jared C Wilson’s “Why Christian Movies Are So Terrible”

Jared C Wilson gets five out of five stars for his review of the state of Christian movies: Why Christian Movies Are So Terrible. He nails it, especially the first point, that Christian movies are made, not by artists, but by propagandists.

Wilson states:

Christian movies are more akin to propaganda than art, because they begin with wanting to communicate some Christian theme — the power of prayer, the power of believing, the power of something — and then the story is crafted around that message. This is true even when the story is something based on a real-life incident. Delving into the depths of human character and motivation is subservient to getting the message across. This is why so much of the dialogue in Christian movies violates the classic writing proverb, “Show, don’t tell.”

Wilson makes the point that many ask why Christian literature no longer has Christian writers of the ilk of CS Lewis, Chesterton etc. However he demurs and insists they’ve been out there:

…they just weren’t writing for the Christian market, because that market does not want art that communicates truth but art that is being used by a message.

Once again the “M” word – the market. Everything is market driven – or at least niche market driven – in these increasingly niche times. In these days of myriad subcultures where you can be a multi-million dollar Christian celebrity with a huge Twitter and Instagram following who no one else outside of church has even heard of.

But men like Lewis and Chesterton, and women like Dorothy Sayers and Flannery O’Connor, had the confidence to write nuance, not because they were unsure of their faith, but because they were completely sure of it. They knew their theology so well and so deeply that the could live with the nuances of life, and its tendency to either untangle the knots in a messy, painful manner, or not untangle them at all, at least not in this life.

Indeed their own personal lives often reflected those messy nuances. Ours do too, but we’re increasingly not allowed to admit that in a church culture that does not understand the grace of the gospel and is content with slogans and memes.

It was also the case for these writers that their eschatology did not require an answer here and now. They knew what it meant to suffer, and they knew that suffering in this age was infused with meaning because of the age-to-come. We can blame theology-lite among evangelicalism, and the explicit and implicit prosperity gospel, for that falling off the radar in general, not just in the Christian arts scene.

FWIW, my favourite movies about the Christian faith are The Apostle (starring and directed by Robert Duvall), Silence (Martin Scorsese), and The Last Temptation of Christ (also Scorsese). And to throw it in there, my favourite book about ministry is the novel Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, a complex Calvinist woman with an intellect and curiosity beyond compare.

Scorsese makes the point (about The Last Temptation) that the primary battle Jesus would have had with Satan was not to be offered something bad, but something good, something good but lesser than the great that God wanted from him.

He notes that there’s nothing bad or unnatural about wanting the love of a woman or a quiet family life, but those things were incredible temptations that would have led Jesus away from his calling.

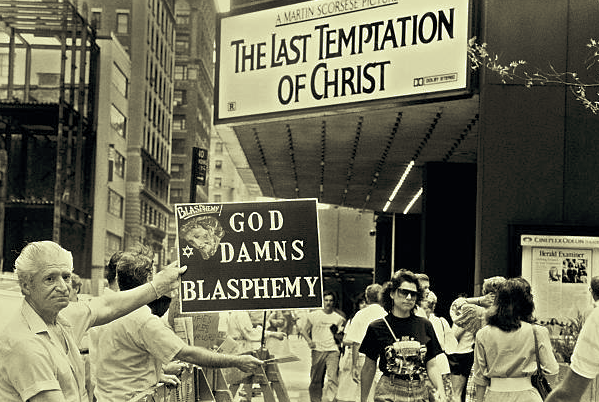

And what were Christians doing outside movie theatres showing this work in 1988? Placarding against it.

Yet time has proven in the three ensuing decades that the things that tempt Christians away from the faith the most are not monstrous evils, but the good things of life that we worship and serve instead of worshipping and serving the Creator. The smile on the face of Willem Defoe’s Jesus on the cross, when he realises the temptation he gave in to was one last vivid hallucination before death, is joyous and sobering at the same time.

Part of the problem is how little value has been placed in the arts by mainstream evangelicalism, by any evangelicalism over the past couple of decades. And coupled with the historic – and now increasing – hostility towards the Christian faith in the movie business, it’s increasingly become harder to navigate that space. Not that it cannot be done, but if it is to be done, it has to be done well.

There’s nothing worse than the starry eyed Christian heading off to the arts world with a sincere, but untested faith, only for them to cave in completely to the world’s vision of the good life in next to no time. Trouble with that is, there’s no one so zealous as a convert, and the post-Christian artistic types can become the most vehement voices against the faith, and they have the artistic wherewithal to get their new found faith across.

Which brings me to the extension of Wilson’s argument, once which I have noted, not among Christian movies in general, but secular movies in general: the increasingly blatant use of propaganda to promulgate the new faith of this secular sexular age.

It’s not simply true that Christian movies are increasingly bad, in the sense that they lack nuance and wish to promote a message, and hence are propaganda. So too are secular movies, and for exactly the same reasons: religious zeal that is looking to evangelise the unbeliever.

In the past of course many movies promoted secular agendas, but as Wilson notes with the best movies, they were capable of doing the “show not tell” thing. But that is changing. And changing in obvious ways. Sure the “show not tell” think is still a Hollywood standard, but the way that the show is showing is, shall we say, increasingly “showy”!

In the past Hollywood’s production values and ability to show and not tell, even when presenting the most obviously anti-gospel frameworks, meant that general culture imbibed those values over time.

Even movies such as Kinsey, which presented a completely photoshopped version of Alfred Kinsey’s sexual deviancy and his tendency to use children as his test subjects for sexual experiments, kept it subtle, subsuming the Sexular culture within a more complex narrative.

But increasingly there’s nothing subtle or nuanced about the messages being presented by mainstream movies either. Which is sad. The best movies are great conversation starters, but when the movie decides to both hold the conversation for you, and come to the conclusions that you should be coming to if you’re the socially healthy modern liberal westerner we all know you should be, then it’s fallen into the same trap Wilson points out in Christian movies – the shift from art to propaganda.

Hollywood, in this culturally dividing times, is increasingly unable to nuance. But nor does it want to. Nor does it seem to wish viewers to empathise with “the religious other” – especially the other of the traditional Christian variety. Such characters increasingly re becoming cardboard cut outs.

Complexity is a virtue in our new world, and it cannot be handed out too liberally, for we may soon find ourselves viewing the new transgressives with a level of regard they are no longer entitled to.

Of course this is not new to Hollywood. Cardboard cut outs were stock standard, ironically, for gay people in many Hollywood movies through the early nineties, and insultingly so. Always camp, always cheerful, always the shoulder to cry on. And that itself was a trope designed to purvey a message; a tell not a show.

It took a TV series, Queer as Folk (first UK and then US versions), to come to the obvious conclusion, that gay people were first and foremost people, with all of the goodness, badness, complexity, ability, stupidity, and sheer bad intent, as everyone else. That series told stories and allowed the viewer to come to her own conclusions.

Yet now, ironically in the hardening secular world, Hollywood is going to increasingly see the world in fundamentalist religious categories; good/bad, black hat/white hat, and the stories will become far less interesting, and will honour the audience far less than they once did. That’s the trajectory we’re on.

The bad person has to be real bad. Dick Cheney has to be really bad in Vice. Any nuance has to be photoshopped out of the picture, as Greg Sheridan noted in The Australian just this very weekend. Sheridan knows Cheney’s real story as well as anyone and the movie cannot manage more than a cardboard cut out of a complex man.

Let’s revisit Wilson’s comment again:

Christian movies are more akin to propaganda than art, because they begin with wanting to communicate some Christian theme.

Ergo so much from Hollywood movies these days. Their tendency is to reduce the nuance as the secular religiosity barometer rises. Why? Because in the all-important battle for right and wrong there can be no nuance! I well remember walking out of the family movie Zootopia, three years ago, having ground my teeth the whole way through its completely unsubtle propaganda pitched at diversity and sexuality.

Indeed as we threw the empty popcorn buckets in the bin, my then fourteen year old daughter listed off the “right on” topics that all too many “woke” English teachers would seize upon when watching the movie with their students. You can read my review of that particular movie here.

Of course this is not to say that good movies are not being made. Many are. It’s just to say that when Christian movies do propaganda, they tend to do it in a cack-handed manner. Everything signals “Propaganda! Fresh Propaganda! Come and get it here!”

And Hollywood? Much better at it. So much better. It can – and has, for decades, made smooth, sweet, beguiling and bewitching propaganda that shifts the way we think, that changes our minds, and our actions, subtly and over time on a matter, and all without us ever realising we have done so. Which is, after all, the point of propaganda, is it not?

(BTW, why not check out a fantastic Aussie site run by Christians about movies, and discussions that can be had around them at reeldialogue.com)

Written by

There is no guarantee that Jesus will return in our desired timeframe. Yet we have no reason to be anxious, because even if the timeframe is not guaranteed, the outcome is! We don’t have to waste energy being anxious; we can put it to better use.

Stephen McAlpine – futureproof

Stay in the know

Receive content updates, new blog articles and upcoming events all to your inbox.