July 29, 2017

Rubik’s Cube, Muscle Memory and The Christian Life

My nine year old son asked me the inevitable “Did they have “BLANK” back in your day?” question recently, holding up a Rubik’s Cube for my perusal.

He has asked me the same about coloured television too, which is more insulting as the cube is nowhere near as ubiquitous as TV. What’s with kids these days? But I digress.

“Course!” I said, grabbing it and casually flicking the segments around and artfully completing the blue side with all four top rows along its edge complete too. Barely looking either.

“You can do a side!” he said, sounding impressed, “How did you do that?“

“Just can,” I sniffed, looking away to polish my fingernails on my shirt.

And then, in the immortal words of Bachman Turner Overdrive, I turned and retorted, “You ain’t seen n-n-nothin’ yet.”

I then proceeded to fill in the second row in a blur of colour and fingers, only getting stuck where I used to get stuck when I was thirteen; the outside corners of the bottom row. I can do the whole thing, but that row is a tricky little so and so. Takes a bit longer.

Honest, I can.

By this time my nine year old was about to sacrifice a votive offering to me, and utter something idolatrous.

“Give me a strategy Dad!”

And that’s when I realised I couldn’t. Or more to the point, a few days of frustration as I realised I couldn’t. I went through it time and time in slo-mo mode, in which he neither got the hang of it, and, worse, I lost my way the slower I went, making him ever more frustrated as we went along.

Why couldn’t I teach him to do what I was doing? Why was it so easy for me to do and so hard to teach? I put it down to muscle memory. The constant habit over many years of picking up a Rubik’s Cube and my hands just knowing how to do it almost unthinkingly.

Not unthinkingly of course. Just seemingly so. My brain is so in tune with the way my hands need to move in order to do a Rubik’s Cube that it’s default mode. I just know and it happens.

One of the great myths that has grown up around Christianity in the post-Romantic period is that habit is somehow a lesser beast, a sub-species of true spirituality. Spontaneity is seen as somehow more worthy of our Christian walk, our Christian prayers, our Christian responses to the gospel.

So doing anything out of habit, anything out of having done it for years and years and years is viewed as suspect and prone to dry orthodoxy and religiosity, or devoid of the Holy Spirit.

Nothing could be further from the truth. In this age of pick and mix Christian involvement, the less than regular church attendance that is the scourge of our late modern West, the major risk is the loss of what I will call “spiritual muscle memory”. By that I mean the stripping away of any habitual practices that, over time, make us who we are, as if by default.

Spiritual muscle memory is what gets us across the vast steppes of ordinary life intact; the huge swathes of so-so life in which our decisions are made, our thoughts are formed, our loves are shaped and our values are gathered. The Christian life is not all mountain tops, nor indeed is it all valleys, much of it is steady plodding, despite what the Facebook memes tell you.

Of course it’s not default is it? Jamie Smith, in his book Desiring the Kingdom states that we are shaped more by what we love than by what we know. But he does not leave it there.

He says that what we love is formed by deeply ingrained habits over time. There is no neutral. We don’t suddenly decide to love something, not in any rich, ingrained manner at least. No, we slowly learn to love something as we do it, so much that at some stage it’s hard to know where our love ends and we begin. It’s true of every habit we form, good or bad. It becomes like the Rubik’s Cube is to me; a deep connection between body and mind that is less unconscious and more subconscious.

Good habits and bad addictions.

Good habits are obvious. Turning up to meet with God’s people week in week out. Just committing every day to God verbally because you do. Sharing meals with fellow believers. Getting up and loving your family in practical ways day in day out. Deciding to serve and love awkward other people (all other people are awkward, just ask other people how they feel about other people).

In other words we don’t love God and love others because you decide to do so one day. We love God and love others because we decide to over many days, weeks, months, years. We learn the habit, the spiritual muscle memory, of loving God and loving others, and so that’s what we do.

Or we don’t, as our addictions tell us. Our vices and self-focus are deeply ingrained habits. We turn, naturally, to our lusts and feed them because of spiritual, emotional and physical muscle memory. We learn to dislike other people and serve ourselves as we do exactly that more and more over time.

Don’t go to an old people’s home and expect old people to be nice. Those grumpy in their youth will be even grumpier, especially as their physical ability to suppress their baser instincts weakens. They’re grumpier now than they were then because they’ve had years of practise! It’s just who they have become. As their surface memory disappears, their deep memory kicks in.

Spiritual muscle memory is the essence of ongoing, daily discipleship. Not that we don’t have to think about discipleship each day, but it’s as we practice practises over time that we are discipled into them and they become not just what we consciously do, but they become who we are. We do that together as God’s people. We do that individually as God’s people.

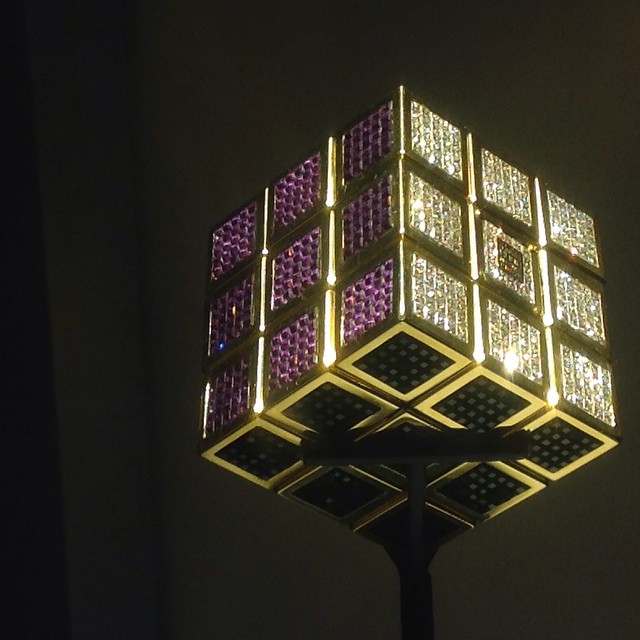

And for the tricky stuff? The besetting sins? The lazy lusts? That’s the third row of the Rubik’s cube. The stuff that we have to concentrate on in order to conquer. Let’s call that ongoing sanctification. And one day, in the kingdom come the last row will click into place, and, thankfully, all the colours will NOT bleed into one, and things will look a little more like this:

Written by

There is no guarantee that Jesus will return in our desired timeframe. Yet we have no reason to be anxious, because even if the timeframe is not guaranteed, the outcome is! We don’t have to waste energy being anxious; we can put it to better use.

Stephen McAlpine – futureproof

Stay in the know

Receive content updates, new blog articles and upcoming events all to your inbox.