January 2, 2023

Was The Pope a Catholic?

With the death of Pope Benedict XVI the Roman Catholic Church lost one of its great intellectuals. Not merely of recent years, but across the centuries. He truly was an amazing man with an amazing mind. His understanding of the cultural pressures those of faith face today was equally great. He saw the enervating nature of secularism without transcendence for what it is.

But Pope Benedict was also a Roman Catholic. No surprises there! But perhaps I have to say it like that. Because, despite some revisionist hopes of evangelicals who admired him, this means he was committed to Roman Catholic theology. Especially around the means by which humans are saved, and consequently, or perhaps because of, his understanding of God’s holy nature.

I have no doubt that Benedict was a deeply pious man, and even today his last words were reported to have been “Lord I love you.” A great way to go out indeed.

But at a time when I have seen a drift towards Roman Catholicism among some, especially younger, evangelicals because of the perception it is holding the line more strongly on ethical matters in the public square (and because it shamelessly offers a “crunchy historicity” that many evangelicals positively flee from), I want to affirm the great soteriological difference between Rome and Protestantism. And it’s not simply because of theology, it’s because of the existential reality of what the gospel actually does!

In fact, painfully, I have watched people I have known well in evangelical ministry break from Protestantism and shift to Rome. And I want to say to them that they’re giving up more – far much more – than they think they are gaining.

Now you can read a far better theological critique of Benedict from an evangelical position here at The Gospel Coalition site by Leonardo de Chirico who pastors in Padova in Italy. It’s a nuanced, generous and compelling piece.

But for me, the assurance of salvation is absolutely central to the reason why Benedict’s theological centre is insufficient, even if his ethical writings and theological insights were astonishing, timely and brave.

Writing in praise of him in The Australian newspaper on the weekend, Tess Livingston quotes from his 2016 book, Last Testament: In His Own Words. Benedict makes this astute observation about life after death:

“God is so great that we never finish our searching. He is always new. With God there is perpetual, unending encounter, with new discoveries and new joy. Such things are theological matters. At the same time, in an entirely human perspective, I look forward to being reunited with my parents, my siblings, my friends, and I imagine it will be as lovely as it was at our family home.’’

A great reminder indeed that the point of the new creation, first and foremost, will be God, while the side benefits will be the good fruits of his creation made new, forever learning and growing beside us.

But Tess Livingston also quotes Benedict approvingly when he says the following:

Never one to presume on God’s mercy, he also wrote that when he encountered the Lord, “I will plead with him to have leniency towards my wretchedness.’’

And that’s where I think the problem lies. You see, pleading with God for leniency when we face him is not the gospel. That’s not good news. At least it’s not good news for me. It’s not good news for those who require – indeed – demand justice for the sinful things that have been done to them.

The gospel is not presuming on God’s mercy,, that much is true, but it is relying on God’s mercy. Leaning on God’s mercy. Falling on our faces before God’s mercy. And where is such mercy found? Not in God’s leniency, but in the sufficiency of the finished work of the Lord Jesus Christ on my behalf.

The beauty of the gospel is that because of the sufficient work of Christ on my behalf on the cross, the holy anger of a righteous God who cannot abide sin, and will not be lenient towards it in a “Oh that doesn’t matter” kinda way, is sated. God’s wrath towards my sin is satisfied because of the cross. The cross does not make God lenient towards sin. In contrast it demonstrates his righteous holy anger towards every iota of it.

Yet because of the cross of his dear Son, and the great exchange that occurred there, God sees me as righteous. An alien righteousness – the righteousness of the Lord Jesus – is on my account.

That’s mercy, not leniency. The gospel – the good news of salvation through faith alone by grace alone – humbles me and glorifies God like nothing else does. And we end up glorifying God because of it, rather than glorifying ourselves.

You see, I look at my own sin and I don’t want leniency. My sin doesn’t deserve it. I see my anger, my laziness, my lust, my dull-heartedness towards those who are suffering, my general ennui and half-baked service of God, and I don’t want God to go “Whatever!” I want him to God “Look at what my perfect Son has done on your behalf and for my glory!”

God’s leniency won’t compel or empower me put my sin aside. But in the power of the Holy Spirit his mercy will!

And not to put to fine a point on it I don’t want leniency for anyone who sins against me. I want justice! Yet if at the centre of God’s character is mercy rather than leniency, then I need to exhibit the same mercy towards others that God has exhibited towards me. That won’t make little of the sin of others, but it will make a lot of the mercy of God.

Look I know what Benedict might be getting at. As I get older I too think about the day of my death more frequently. Every day as it happens. I look at the slowness of my sanctification and I wonder “Really? Shouldn’t I be further along than this?” And besides, my death could be today. What then keeps me from despair, or the self-deceptive salve of God merely being lenient towards my sin on my final day? It’s not the hope that he is lenient, but the conviction that he is righteous, and at the centre of that righteousness is the sufficient work of His Son.

Yet if the head of the Roman Catholic Church ultimately presses into leniency for his acceptance by God at final judgement, then it stands to reason that that’s because the centre of the theology of that church may indeed be pressing into that as well. While I have many Roman Catholic friends who undoubtedly love Jesus and will be singing his praises with me around his throne, that will be despite what is at the centre of that church’s theology, not because of it.

So I don’t need God to be lenient towards my wretchedness. That’s no hope or comfort for me in this life or the next. I need him to be gracious and merciful, on the basis of the work of salvation achieved for me by his Son, and nothing else. Incidentally, if this is causing some consternation for you, there’s a helpful book by Aussie pastor now ministering in Dubai, Ray Galea who was formerly a Roman Catholic of Maltese heritage. It’s called Nothing In My Hand I Bring: Understanding Differences Between Roman Catholic and Protestant Believers.

I don’t want to sound too churlish towards someone who I consider to have been a good man and a theological giant, but if I want a lenient God I don’t even need to try Christianity. Every other religion will give me that as well. And I say that to the increasing number of younger evangelicals toying with Roman Catholicism on the basis of it giving them that extra push to endure a souring secular culture.

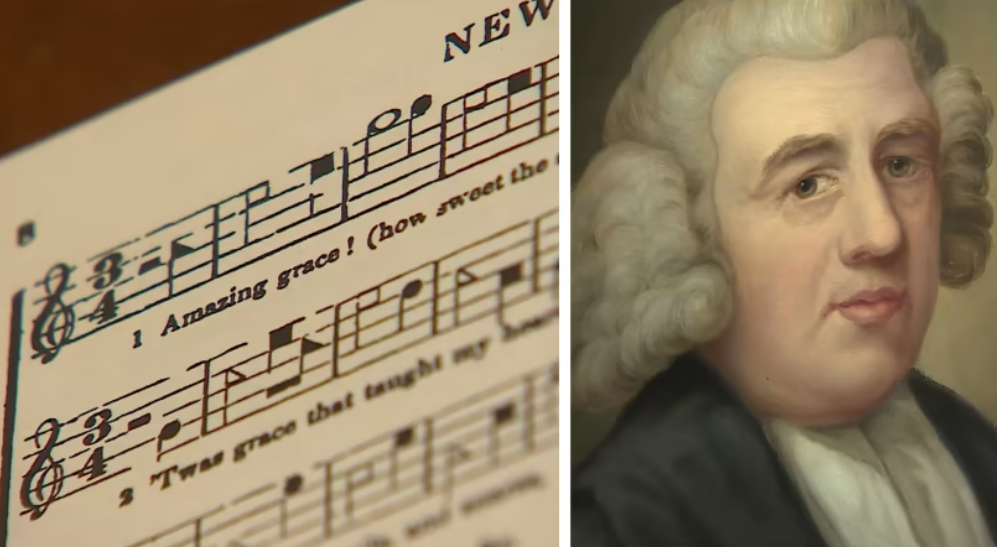

So it’s timely, as I finish this post, to remember that this past New Year’s Day also marked the 250th anniversary of perhaps the best known hymn of all time, Amazing Grace. Do we need a reminder of the difference between Benedict’s view of how God would view his wretchedness and how John Newton saw it?

Amazing grace, how sweet the sound/that saved a wretch like me

Lenient gods are not worthy of our hymns. What kind of God is? What kind of God will ensure that we continue to sing this hymn another 250 years should Christ tarry?

Here’s the kind of God: A merciful and gracious God the Father who dwells in holy, unapproachable light, yet out of great love for His sin-ridden and rebellious creatures sacrificed his Son; a willing Son who through his incarnation lived the life we did not, yet died the death we deserve,d and in so doing delivered the great exchange on the cross for our sakes; the same Son who now glorified, shares the benefits of his atoning death and resurrected life with us by the power of the indwelling gift of God’s Holy Spirit.

Such a merciful and gracious God is worthy of our praise.

Written by

There is no guarantee that Jesus will return in our desired timeframe. Yet we have no reason to be anxious, because even if the timeframe is not guaranteed, the outcome is! We don’t have to waste energy being anxious; we can put it to better use.

Stephen McAlpine – futureproof

Stay in the know

Receive content updates, new blog articles and upcoming events all to your inbox.